George Frideric Handel had no time to waste. Other West End impresarios were already promoting their upcoming winter subscription series at the beginning of summer 1734. Evicted from his long-time base of operations, the King’s Theatre, by his infuriatingly wealthy nemesis, The Opera of the Nobility, London’s founding father of opera seria was out on the street. It was an intensely embarrassing predicament. Despite a recent dip in box office profits, the local appetite for Italian musical extravaganzas was still healthy. Not only did Handel have no fresh manuscripts on hand to satisfy his hungry audience, he had nowhere to feed his fans.

To his immense relief, John Rich, manager of the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden rushed to the rescue at the eleventh hour, offering to host George Frideric’s embattled company at Rich’s modern, well-equipped premises. Lease duly signed, the enterprising maestro threw himself into his work. By early September, Handel had set the final notes to a chilling new 3-act thriller, musically pointed, narratively blunt.

Though modestly well-received when first presented on January 8, 1735, Ariodante, for all its high stakes drama and lust, soon flamed out, languishing in obscurity for over 200 years. Untypically for Handel, the lurid, expressly 18th century gothic piece is ironically more popular in today’s jaded world than it ever was in its creator’s lifetime.

Vastly inflating Handel’s salacious tale of moral collapse to even more sensational dimensions, the Canadian Opera Company unleashes a brutal, savage treatment on Four Seasons Centre ticket holders. Waves of inappropriate titters and misdirected bravos on opening night signal some considerable confusion on the audience’s part.

Director Richard Jones’ perverse, post modern production premiered at the Festival d’Aix-en-Provence in 2014 has its legion of cheerleading apologists.

Opera Going Toronto is not among them.

Handel’s libretto, loosely rooted in poet Lodivico Ariosto’s 16th century epic, Orlando Furioso with text “borrowed” from playwright Antonio Salvi’s 1708 follow-up, Ginevra, principessa di Scozia, is given an updated reading.

A rugged, secluded Scottish isle. Ariodante, a frequent visitor from a neighbouring shore, is to marry his lover, Ginevra, the resident laird’s daughter, and become the clan’s new chieftain. The evil Polinesso, an ambitious pretender masquerading as a priest, enlists the aid of an impressionable maid, Dalinda, to destroy Ariodante by casting doubt on Ginevra’s faithfulness. Secretly drugging her, villain and accomplice strip off her wedding gown. Ensuring that Ariodante is watching outside the door, Polinesso slips back into Ginevra’s room. Dalinda, veiled and dressed as Ariodante’s fiancé, is viciously raped. Ariodante rushes into the night to throw himself into the sea. His brother, hot-headed Lurcanio, who has accidentally witnessed Ginevra’s supposed treachery, demands revenge, rallying the community against her. Polinesso, deceitful to the end, engages Lurcanio in a knife fight, scheming to win Ginevra’s devotion by seeming to defend her honour. Dalinda, guilt-ridden and devastated, races out of the laird’s ancestral lair. Lurcanio kills Polinesso. Ariodante bursts onto the scene having miraculously survived his attempted suicide. Dalinda has told him everything during a chance encounter in the yard. Ginevra, alienated and repelled by her cruel abandonment by lover, father, clan, shrinks from any and all gestures of reconciliation. Suitcase in hand, she heads for the nearest highway to thumb a ride.

The story, like so many others in opera, creaks and sways under the weight of the slightest scrutiny. Ariodante’s dramatic superstructure is built on little more than feelings of shame and betrayal, not always firmly secured to character. Virtually all principals are felled by precisely the same emotional affliction once the rickety mono plot is set into play. There are no narrative tangents.

Jones’ directorial response to the abiding issue of how best to support the shaky dramaturgy is to slap on a thick layer of shock value. The result is both prurient and perverse. Strewn with episodes of graphic hate sex and misogyny, bruising physical assault, rape, this violent, combative Ariodante is as lewd as it is explicit, the theatrical equivalent of tabloid journalism. Controversy, however, does not necessarily imply creativity. And voyeurism most certainly does not equal insight.

Even the set feels gratuitous.

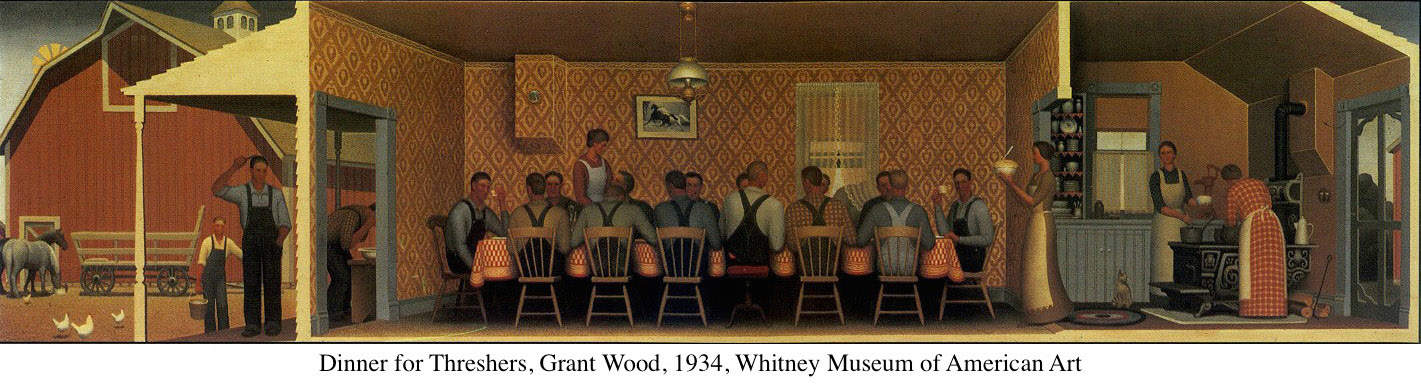

In 1934, Idaho-born realist Grant Wood painted a scene long remembered from his childhood, a powerful, panoramic memory featuring a group of 14 farm labourers seated at a long harvest table sharing a meal. With its idealized evocation of American democratic values overhung by the echo of the Last Supper, Dinner for Threshers hauntingly captured the spirit of the Midwestern experience, durable, muscular.

Jones and British design guru ULTZ have both openly acknowledged that Wood’s canvas animated their vision of Ariodante’s rude tribe of reclusive Scots. While the creators’ taste in 20th century neo-folk art may be impeccable, the admission does not disguise the fact that the imagery and tableau so closely replicated on stage is grossly misappropriated.

Appearing in the title role in this relentlessly auteur-driven production, mezzo-soprano Alice Coote brings moments of welcome relief, singing with rich, genuine Handelian poise. Scherza infida (“Laugh, unfaithful woman”), arguably Ariodante’s most resonant aria, a desperate outpouring of hopelessness, is delivered with pure, unaffected emotion.

Coloratura and improvisation in the hands of other cast members, unfortunately, are less genuine, tentative at best, often halting. Handel is not for every artist.

Inappropriate voice types aside, all singers demonstrate an admirable investment of dramatic energy.

Canadian Opera Company music director Johannes Debus does valiant battle in the pit, leading with great determination while struggling to spark vivacity. The addition of twin harpsichords and a theorbo does not transform a polished, homogeneous contemporary opera orchestra into the vital, spontaneous Baroque band so soundly implied by Handel’s vibrant, frequently rough and ready score.

At the end of the evening, Ariodante is governed, not so much by paradigm shifts, a game changing re-alignment of boundaries, as by a frenzied shaking of the goal posts. Gone are the ballets so carefully custom-crafted by Handel at the close of Acts I and II. Lights up on puppet shows starring kite-flying babies and a pole-dancing Ginevra.

After endless hours of contrivance, the current COC production becomes a weary grind.