The opening visual, a Google satellite map, centres us in time and place, the sweeping digitized view of downtown Toronto oddly suspenseful as the serene panorama slowly expands before our eyes. Panning west north westwards from the understated grandeur of the Four Seasons Centre, the prosperous, fashionable streetscapes of the central core slowly lose immediacy and drift into the distance. A poignant measured overture overlaid with tempered horns plays on. The scene dissolves to an undistinguished mid-rise apartment building spied in full frame close-up. Blank open-eyed windows reveal an assortment of inhabitants of all ages busily occupied with the minutiae of everyday life. It is here on the ground floor in a worn out unit that we begin.

Welcome to the world of Hansel and Gretel, an intensely contemporary, all-original Canadian Opera Company presentation, touching and tender, transcendent and down-to-earth, Engelbert Humperdinck’s mythical 1893 märchenoper (fairytale opera) vividly re-imagined. Sparkling with energy, rich in special effects, gleaming with musicality, director Joel Ivany’s breathless 100-plus minute update further frees Humperdinck and librettist sister Adelheid Wette’s adaptation from the grisly clutches of the Brothers Grimm, refashioning it into a whirlwind celebration of the ageless power of childhood.

Like all successful drama, medieval miracle cycles to 21st century music theatre, Hansel and Gretel relies on a network of polar attributes to propel story. Wily, introverted Hansel. Impetuous, strong-willed Gretel. Narrative themes, like principal characters, are ultimately opposed. And almost certainly guaranteed to spark conflict. Poverty and deprivation drive the two young protagonists into the witchy realm of transgression and self-indulgence. The temptation to deliver a veiled moral message proved irresistible for a latter day Romantic like Humperdinck.

Ivany sees his Hansel and Gretel through considerably more charitable eyes. The inner city is their wilderness. The spectre of genuine hunger haunts them. Their mother, Gertrude, walks a vicious knife-edge of cutting emotions — bitterness, despair, anger. Anxiety and stress threaten to crush her capacity to cope. Father Peter, on the other hand, a failed handicrafter, maker of homemade brooms, lives in a state of perpetual denial, an incorrigible boozy optimist, good-hearted, impractical. And yet, despite or perhaps because of the daily struggle to simply survive, husband, wife and children still cling to one another.

But literal (and literary) reality, however acutely observed, only propels Ivany’s vision of scenario so far. This very urban, very sociological Hansel and Gretel very quickly transcends the limits of unblinking realism and enters a universe of fantasy and dream. Surrender to imagination, the increasingly extravagant pattern of action and imagery beckons from the stage. Witness the here and now as a once-upon-a-time child. Feel the magic. Breathe from the soul.

And so the stage is set for the enactment of an elaborate pantomime, a secret parental plan to lift Hansel and Gretel’s spirits involving friends and neighbours, young and old, in the building that is the children’s bounded world. Part communal act of kindness, part diversion from the ceaseless grind of subsistence, part declaration of kinship, for a few brief, magical moments, love and compassion overwhelm fear and worry. Fairytale gives rise to fairytale. Hansel and Gretel’s play turns to play.

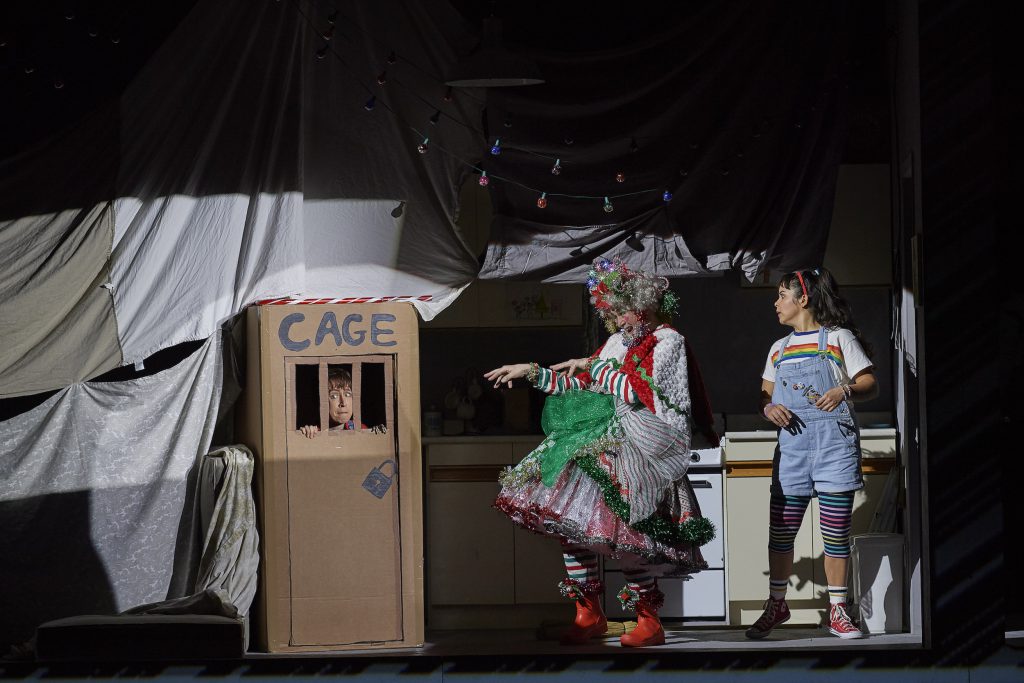

An upstairs apartment, home to a misunderstood recluse and his hoard of valueless treasure, becomes the eerie Ilsenstein, an endless deep dark forest. A sympathetic building superintendent becomes a bearded die Knusperhexe (the wicked witch). A group of Hansel and Gretel’s friends gathered for a sleepover assume almost angelic proportions, keeping watch on a brilliant starry night. Ivany’s nods to divinity throughout the opera are as tranquil and unassuming as his faith in caring family and community values is overt.

Hansel and Gretel’s story is, of course, at the forefront of artistic attention here but any number of other micro-scale dramas are also very much in play during the course of this busy narrative journey into the dominion of make-believe. Set designer S. Katy Tucker’s scrupulously detailed cutaway apartment block bustles with life, a multi-storey collection of tenants engaged in an intimate miniseries of domestic vignettes. The sense of shifting spectacle and tableau is utterly captivating. JAX Messenger’s warm, homey lighting and Tucker’s stunning animated video projection greatly contribute to the overall air of enchantment so prevalent throughout the evening.

Conducting with customary sensitivity and refinement, COC Music Director Johannes Debus leads a glowing 70-plus player orchestra in a truly lustrous performance of Humperdinck’s gloriously expressive score. Carefully constructed on a foundation of Wagnerian-inspired fundamentals, Hansel and Gretel’s meticulous, highly polished musical architecture is distinguished, not so much by robust heroic themes and ringing leitmotifs (although both elements are present to some extent), rather by its reliance on melody and lyricism. Chromaticism is largely replaced by gentler, more yielding patterns of tonality with little or no diminishing of orchestral colour. Folk tunes, popular dances, a sacred anthem, Humperdinck accommodates them all in music of almost limitless variety and depth. The towering orchestral interlude that precedes Act III, layer on layer of nature and night, is nothing less than a masterpiece of orchestration played by Debus and COC instrumentalists with immense vitality overseen by a dazzling cosmos.

Partnered in the lead roles of Hansel and Gretel, mezzo-soprano Emily Fons and soprano Simone Osborne seize playful command of the vast Four Seasons Centre stage at lights up and never surrender control. Graced with bright, sunny voices and endlessly energetic stage manners, the two seasoned young artists delight, inhabiting the mischievous duo to persuasive effect, all skipping and scampering and wide-eyed wonder. Quietly gathered side by side for Humperdinck’s much-loved Abendsegen (The Evening Prayer), the pair all but stops the show with a deeply stirring rendition of a piece often associated with Christmas by virtue of Hansel and Gretel’s enduring status as a traditional seasonal offering.

Mezzo-soprano Krisztina Szabó appears as Gertrude. Baritone Russell Braun sings Peter. A-list artists both, Szabó with her honeyed timbre, Braun with his high-note friendly instrument, launch Ivany’s restless mise en scène on its arcing trajectory with great strength and reassurance. Vocally dominating the first act of the opera, the two literally slip into the shadows for essentially the duration, stepping out of the spotlight to quietly rearrange furniture, string Christmas lights, muster supernumeraries. That they do so with such flair and obvious enthusiasm is testament to the pair’s professionalism.

Soprano Anna-Sophie Neher is the Sandman, magical harbinger of sleep, reappearing as a coffee cup carrying Dew Fairy, quintessential morning sprite.

Tenor Michael Colvin is The Witch, comic and ominous by equal turn. Few have surely ever wielded a broomstick or cast an evil spell quite so convincingly.

Singing with fine heartwarming radiance and poise, the young artists of the Canadian Children’s Opera Company close the proceedings with a shining rendition of Humperdinck’s soaring chorale, Erlöst, befreit, für alle Zeit! (“We’re safe, we’re free and always will be”).

Hansel and Gretel may very well be an opera uniquely populated by children largely told from their singularly refreshing point of view but it is not one exclusively written for them. With its unwavering focus on vibrant contemporary tropes and abiding concern for urgent inner city issues, this, the COC’s very first Hansel, embraces a broad audience. We adults are gingerbread children, too. This lovely, entrancing production, focused yet whimsical, telling but diverting, opens our eyes to all that we once were and can be again.