On October 31, 1517, Martin Luther nailed his Ninety-five Theses to the door of the Schlosskirche in Wittenberg setting alight the theological firestorm that was to scorch the Roman Church. In many ways, the force of his outrage, his furious denunciation of hypocrisy and moral blindness, still holds pressing meaning for Christians of all denominations 500 years later.

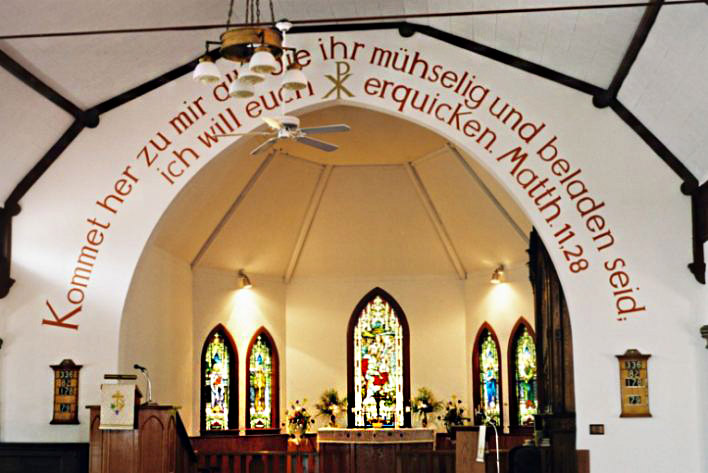

On this the quincentennial of the Reformation, the Theatre of Early Music, Orchestra and Choir, channelled past and present with an intensely intimate concert at St. George’s Lutheran Church showcasing Johann Sebastian Bach’s timeless Cantatas 79 and 80. Penned in praise of Luther’s declaration of paradoxically plain-spoken Christian values, the two mighty works, Gott der Herr ist Sonn und Schild (God the Lord is sun and shield) and Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott (A Mighty Fortress Is Our God) sparked powerful performances from singers and players alike.

Presented in reverse chronology, arguably the more theatrical of the two works, Cantata 79, closing the program, charismatic conductor Daniel Taylor leapt headlong into the swelling chorale that launches Cantata 80 heavenwards. First written in 1724, revised in 1730, Bach’s mighty evocation of a hymn, words and melody by Luther himself, sends believers into stirring vocal battle in defence of Christ’s true message. Scored for four-part choir, an equal number of solo voice types plus compact period ensemble —strings, oboes and continuo — Ein feste Burg quickly marshalled forces, tenors and alto reinforced by sopranos and basses, all surging forward in intricate contrapuntal step.

The second movement, Alles, was von Gott geboren (All that is born of God), struck a more lilting note, sung with tripping joyfulness by bass-baritone Daniel Lichti, accompanying embellishment by choral soprano and oboe both voicing the second stanza, Mit unsrer Macht ist nichts getan (By our own power nothing is accomplished).

A mellow secco recitative by Lichti followed by Bach’s touching fourth movement, Komm in mein Herzenshaus (Come into my heart’s house), a tender soprano aria poignantly sung by Ellen McAteer brought us to the midpoint of the cantata, Bach’s long lines of twining melisma traced with superb finesse. Cello accompaniment by Margaret Jordan-Gay supported by Matthew Larkin’s gentle chamber organ enchanted.

Und wenn die Welt voll Teufel wär (And if the world were full of devils), an untypically unadorned choral melody sung in unison lies at the core of Bach’s setting of Luther’s rousing battle hymn of the Reformation. Tenor Owen McCausland, no stranger to Toronto opera stages, joined by Taylor as countertenor continued Bach’s measured advance in a graceful, dramatic rendering of Wie selig sind doch die, die Gott im Munde tragen (How blessed are they, who bear God in their mouths).

A fervent chorale, Das Wort sie sollen lassen stahn (They shall pay no heed to God’s word), ended the cantata with an uplifted proclamation of communal resolve.

Bookended by the two impassioned Bach compositions, Vivaldi’s Concerto in D Minor, though utterly divorced from the cause of Reformation, formed a somewhat startling though clearly much appreciated musical intermission, a flash of Venetian razzle-dazzle to Bach’s more sober purpose. First violin Jeanne Lamon’s glowing virtuosic treatment of the Largo was particularly affecting, finely nuanced and golden.

Returning to 1723 Leipzig, Cantata 79 opened with a majestic invocation, a towering call to prayer, played by an expanded TEM orchestra augmented by Baroque horns and flutes accented by timpani. Ringing fanfares echoed from the apse, ceremonial woodwinds and strings evoking a sense of grand occasion, soaring voices emphasizing the unshakeable optimism of Bach’s triumphant affirmation of faith.

Performing the cantata’s first aria, an intimate reiteration of the larger prevailing theme, Gott ist unsre Sonn und Schild (God is our sun and shield), mezzo-soprano Gena Van Oosten brought exquisite warmth and vibrancy to the piece, qualities mirrored in Ruth Denton’s lovely obligatto oboe partnering, singer and player in radiant conversation.

Timpani and horns made a determined reappearance in the strapping chorale that followed, building on the march motif so resoundingly stated in the first movement.

Returning for a characteristically clear-voiced presentation of the quintessentially Reformation-minded recit, Gottlob, wir wissen den rechten Weg zur Seligkeit (God be praised, we know the right way to blessedness), Daniel Lichti confidently swung open the doors to a gloriously lyrical duet.

Meticulously crafted for bass and soprano, Gott, ach Gott, verlass die Deinen nimmermehr! (God, ah God, forsake your people never again!) strikes a distinctly quasi operatic chord, the two voices, resonant and compelling, actively rebounding off one another. Lichti and soloist Agnes Zsigovics brilliantly inhabited the piece.

With a simple heartfelt choral appeal to God, Erhalt uns in der Wahrheit (Keep us in the truth), the all-too-brief 70-minute tribute to Bach’s genius drew crisply to a close.

Addressing the audience at a lull in the program, Theatre of Early Music’s Maestro Taylor movingly captured the spirit of the evening, calling it, quite simply, “a coming together in difficult times”. Surely a concert can have no greater purpose.

* * *

Photo: St. George’s Lutheran Church, Toronto