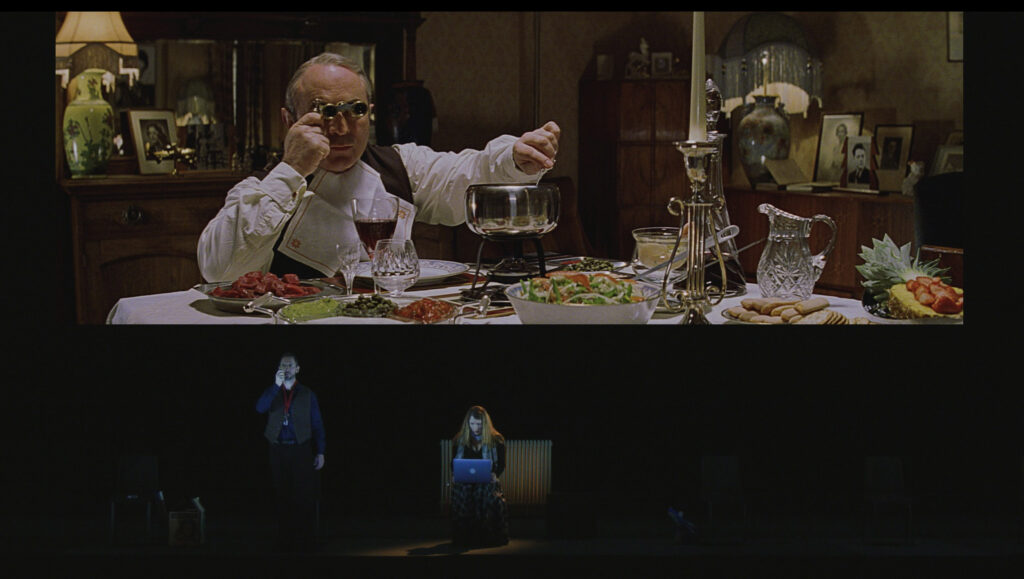

A man, limbo-lit in the darkness. A vast empty space. An open laptop glows in the shadows. The man prepares for the night to come. Secrecy engulfs him, his every move measured and precise. A mystifying potion is prepared. Seven chairs are meticulously arranged in a long orderly row. A film plays on a monster screen above him. The man pays only passing attention. He knows the story well. Images beat down on him, a crushing montage of fractured scenes — ominous, cryptic, troubling. A confused young woman newly arrived from across the sea. A soft-spoken little man in a raincoat driving a curiously outdated little green car. A classic cooking show hosted by a vivacious 60s TV personality watched through opera glasses. A delectable rack of lamb, trimmed, trussed, roasted and devoured.

A second character, a woman, arrives on stage. The man is clearly expecting her. She is carrying a backpack. The man opens it and removes a pair of opera glasses. A portrait of the cooking show host is produced. A carving knife is sharpened. Film and stage, objects and action, increasingly mirror one another. The boundary between fiction and fixation blurs and begins to dissolve.

Or so the prologue to Atom Egoyan’s relentlessly enigmatic treatment of Hungarian-born Béla Bartók’s 1918 expressionist sensation, Bluebeard’s Castle, would seem to suggest.

Repurposing his grimly psychological 1999 feature, Felicia’s Journey, as both foreground and backdrop, the much acclaimed Canadian cineaste brings an inconvertibly Hitchcockian POV to the Canadian Opera Company’s latest digital offering, an intensely demanding creative rescue mission targeting an enduringly problematic work.

A wry commentary on the nature of film and music theatre as allied experience, the mutability of narrative, the precariousness of conveyed sensation, Egoyan’s Bluebeard substantially shifts the burdensome weight of resonance and meaning from dated gothic thriller to more contemporary, if no less unstable, operatic ground. Myth and metaphor, symbolism and psychosis — nothing is fixed. Nothing can be assumed. Expectations are repeatedly foiled.

The mirroring, however cloudy, of two apparently unrelated stories in the name of artistic revisionism is quite clearly a high risk proposition. The sense of dramatic jeopardy at play is palpable. Parallels are neither strict nor organic, Egoyan subjecting Felicia’s Journey to a considerable degree of robust editing to bring it and Bluebeard’s Castle into some semblance of alignment.

Congruency here is a matter of high concept on Egoyan’s part, the linking of opera antagonist to central film character in a horrific display of the former’s ghastly all-consuming fantasies rendered larger than life. Overt pre-existing operatic paradigms are, needless to say, bundled into half-hidden corners or simply discarded.

Bluebeard (Bluebeard’s Castle): serial killer

A man of abiding mystery. Wealthy. Charismatic. Darkly handsome. Moody. Background and occupation unknown. Intensely private. Wholly self-preoccupied. A lover of ritual. Poetic. Wildly imaginative. His mind is his castle. Freakishly obsessed with the film, Felicia’s Journey. Unapprehended murderer of three former wives.

Joe Hilditch (Felicia’s Journey): psychopath

Meticulous catering manager at a Birmingham stamping plant. Lives alone. Drives a vintage dark green Morris Minor. Mother, long deceased BBC3 celebrity chef, Gala. Childhood issues include maternal bullying, feelings of failure. Cooks enormous elaborate meals while watching decades-old recordings of his mother’s how-to series, Bon Appetit. Bodies of eight young women buried in his garden.

Egoyan’s attitude to media and technology, a staple feature of his perennially disquieting filmography, assumes a prominent role in this haunted mise en scène.

Rather than relinquish the traditional seven epic keys to a physical fairytale castle to his new bride, Judith, Egoyan’s Bluebeard furnishes her with a succession of USB sticks. Each launches a different pre-recorded mpeg of a single discrete scene from Felicia’s Journey. Each scene, in turn, reveals a different allegorical aspect of Bluebeard’s fevered psyche. Or so Egoyan would appear to have us understand. Absolutes here are in short supply.

Less abstractly, Hilditch’s world is positively stuffed with infinitely more utilitarian means of communication, albeit from the distant past. Vinyl LPs, videocassettes, black and white snapshots, a portable TV set. Trapped in a time warp in the shrine to Gala he calls home, Hilditch as hopelessly damaged man-boy generates a compelling degree of empathy, a condition Bluebeard seeks to apply to himself. Perhaps.

Appearing as the opera’s tormented anti-hero, international bass-baritone star, Kyle Ketelsen presents us with an unconventional Bluebeard, compromised and vulnerable, singing with sensitively gauged notes of remarkable clarity and pathos.

Krisztina Szabó is Judith. Forcefully engaged and centred, the fine Toronto-based mezzo-soprano turns in a performance of great inner strength, a woman who refuses to be a victim, her voice ringing with resistance.

Resident music director Johannes Debus conducts a mammoth COC orchestra off screen, throwing open the harmonic windows to Bartók’s unique folk-flavoured, impressionist-laden score.

Maddeningly arcane at times, shamelessly auteur-driven, discomfiting and hypnotic, Atom Egoyan’s Bluebeard’s Castle exasperates and enthralls in almost equal measure. What begins as a perilous experiment to test the limits of film and opera ultimately yields broader compelling results dispelling a good deal of the male toxicity that has long clung to the work. Demanding, emotionally excruciating, this is a production of considerable transformative power. The ending comes as an eye-opening surprise.

* * *

To access all COC opera and concert streams, register for free digital membership at COC.ca