The experience of Opera Atelier’s newest production, Der Freischütz (The Marksman), feels much like opening a time capsule and discovering a cache of antique artefacts, a good many of them still surprisingly in use. Taking a traditional German ghost story as the basis for their inspiration, composer Carl Maria von Weber and his librettist, Friedrich Kind, combined elements of horror and folktale to create a strange haunted — and haunting — pastiche. Premiered at Berlin’s Staatsoper in 1821, the bizarre goth opera was an instant sensation, translated and re-staged by Berlioz twenty years later in Paris. Contemporary audiences gasped and swooned. Although only sporadically performed today, Freischütz still strikes home, even if coloured with the occasional campy overtone.

Curtain up. Seventeenth century Bohemia. Young Max, a marksman, must prove his ability in order to succeed as head forester and win the hand of Agathe whom he loves. Alas, his skill with a long gun has become less certain of late. Cast deep into self-doubt and despair, Max is an easy target for Kaspar, a fellow marksman, who offers proof of a magic bullet guaranteed to hit its mark. Little does Max know that Kaspar has traded his soul to the devil, Samiel. The two have made a pact. Kaspar will provide Samiel with fresh new followers in return for a sharpshooter’s unfailing aim. More magic bullets are waiting to be cast deep in the neighbouring forest, Kaspar promises. Max’s victory at the upcoming shooting match will be assured. Max agrees to meet Kaspar at midnight in the dreaded Wolf’s Glen.

Later that evening. A house by the woods. Agathe shares a feeling of unease with her companion, Aanchen. A holy hermit has given her a bouquet of roses to ward off the evil he senses gathering around her. Aanchen does her best to cheer up her friend but Agathe’s apprehension only deepens.

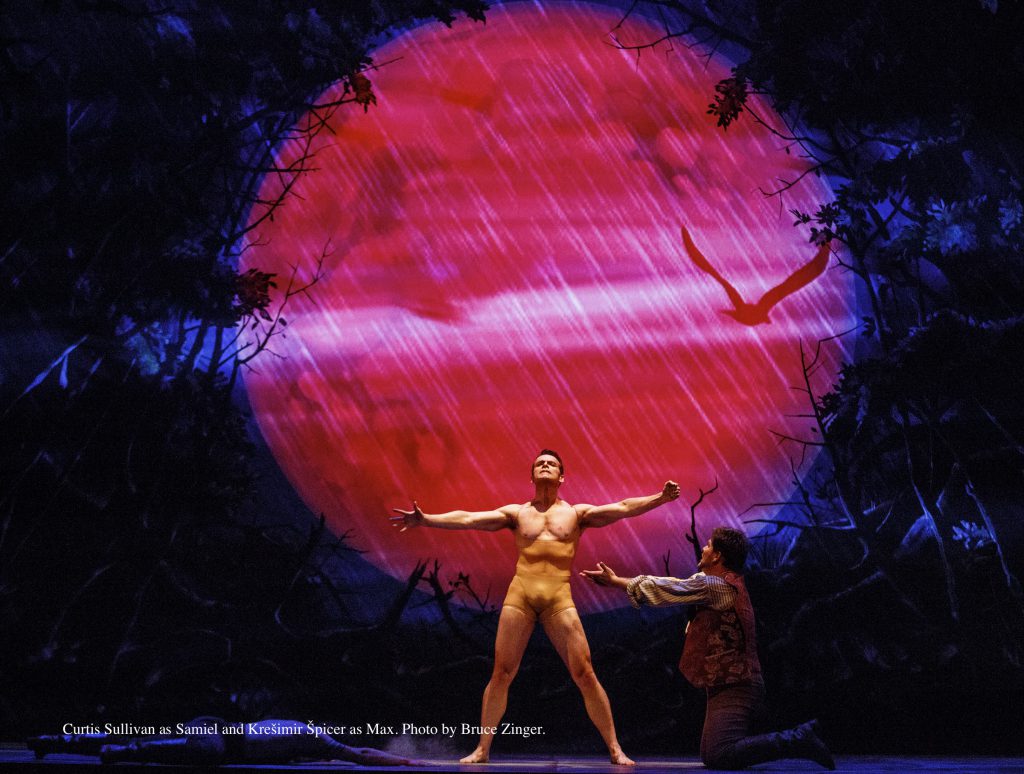

The Wolf’s Glen at night. Kaspar summons Samiel. Max appears nearby. His mother’s spirit cautions him not to approach. Samiel responds with a trick and conjures a vision of Agathe drowning. Max is lured closer. Encircled by hideous wild spectres, Kaspar casts the magic bullets in the devils fiery furnace. The last of the bullets will be under Samiel’s control.

The next morning. Agathe has had a nightmare. She had been turned into a dove, she confides to Aanchen, only to be shot dead by Max. Aanchen tries to lighten Agathe’s mood on her wedding day but no one laughs when a funeral wreath is found in place of the bride’s bouquet.

The marksmen’s match. The Prince has arrived to judge the event. Summoning Max, he instructs him to target a dove perched high in a distant tree. Max takes aim and shoots. Agathe screams and falls to the ground. Max’s gun has misfired. But it is Kaspar who has been fatally hit. He has been double-crossed by the devil. Kaspar gasps his last breath. Agathe revives from her faint. The Hermit enters and, denouncing the contest as an unfit trial of moral worthiness, counsels forgiveness. Despite flirting with the black arts, Max remains pure of heart, the holy man insists. All ends happily as the repentant marksman and Agathe fall into each other’s arms.

Pure classic horror fiction. Mary Shelley might have written it. Or the Brontë sisters. Or Edgar Allan Poe. Broody heroes, innocent heroines, dark sinister settings — early nineteenth century audiences devoured gothic tales like Halloween candy. And truth to tell, so do we. Storylines can be as graphic as the characters that haunt them and Der Freischütz is rich with memorable types. Is mad Kaspar — possessed, ruthless, anti-social — really that different from the Joker? Could Agathe be a Bella? What stirs in the shadows of Freischütz continues into the Twilight series.

In many ways, Der Freischütz is more of a bridge than a ground breaker to present-day eyes and ears. Weber may have been born in the Age of Enlightenment but it was the Romantic Era in which he worked and thrived. Gone was the old belief that eighteenth century science could supply answers for everything. The Napoleonic Wars had blown a hole in much of Europe’s self-confidence. A new day had dawned. Liberate the natural order and anything was possible. Music exploded with new forms of expression. But faint blasts from the past continued to be heard. An echo of Mozart’s Cosi fan tutte from 1790 drifts through Agathe and Aanchen’s solos and duets. Fiordiligi and Dorabella live on in Weber’s clear, harmonious melodies.

Just as the musical arc of Der Freischütz bridges backwards, it also spans forwards. Had the father of native German opera written the Kaspar role for a heldentenor instead of a baritone, Richard Wagner, who greatly admired the work, might very well have been scooped. There is an unmistakable hint of Weber underlying both the musical and dramatic flavour of The Ring. And Wagner would have been the first to admit it.

Historically informed opera has always been the foundation of Opera Atelier’s mandate. This dazzling new offering from the company is most definitely a reflection of a bygone age. But it is much more, as well. Singing, dancing and music are exceptional in and out of any context. Meghan Lindsay’s lovely modulated soprano is the perfect instrument to express the range of Agathe’s surging emotions. Second principal soprano, Carla Huhtanen, employs an effortless, floaty technique endowing her Aanchen with an utterly irresistible playfulness and charm. As Kaspar, Vasil Garvanliev is equally adept at leaping from deep notes of menace to piercing cries of anguish, a strong, confident baritone with an astonishing range. But it is Croatian tenor Krešimir Špicer who truly anchors this production. The role of Max, a central vocal presence for virtually the entire opera, demands not only a profoundly durable delivery system but also a supple nimbleness, a toned athletic style, a marathoner’s voice. Špicer has it all.

Elsewhere onstage, choreographer, Jeanette Lajeunesse Zingg, does fine work in Freischütz, weaving her dancers seamlessly through the action, punctuating Weber’s multi-dimensional music with moments of well-motivated spectacle and drama.

On the podium, conductor David Fallis leads Toronto’s Tafelmusik Orchestra with great energy and insight resulting in consistently strong playing from curtain to curtain although a certain hint of raggedness from the horns does tend to intrude from time to time. A technical hitch, perhaps? Tafelmusik’s valveless brass instruments are frequently asked to carry nearly the full weight of Weber’s highly faceted nineteenth century score and, for the most part, they succeed admirably.

Credit also to set designer, Gerard Gauci, and lighting designer, Bonnie Beecher, for their stunning use of video projection. The magic lantern-like effects, the high tech stagecraft of Weber’s day, project a singularly eerie atmosphere into the dark corners of this astonishing presentation.

With this brilliantly realized Der Freischütz, Opera Atelier breaks through every artistic wall surrounding the programming of lesser-known early opera in today’s HD environment. Marshall Pynkoski, co-artistic director of the company, brings a keen intelligence to production and performance. The work, arguably Pynkoski’s best to date, is a timeless reminder of what opera is and always should be — passionate, artistic, transformative. Der Freischütz is a triumph.