In the summer of 1780, Mozart received momentous news. Elector Karl Theodore of Bavaria had contracted the ambitious 24-year old to write a new opera to debut at carnival-time in southern Germany. Mozart was delighted. And hugely relieved. Over two years of tireless self-promotion had finally yielded a prize court commission. The timing could not have been more opportune.

Still smarting from the failure of his courtship of rising soprano Aloysia Weber — older sister of eventual wife Constanze — Wolfgang Amadeus was feeling singularly isolated and abandoned. Life as concert master and organist to domineering Prince-Archbishop Hieronymus von Colloredo in remote Salzburg was proving increasingly suffocating. Capped by the wearisome weight of his eternally fraught relationship with his father, Leopold, and the still painful memory of his mother’s death two years previously, Mozart’s spirits were on the verge of collapse.

Reinvigorated by the prospect of a brighter, fresher future of his own design, the eager young composer scrambled to board a hired coach to Munich. The product of his time there would be a work like nothing he had created before.

Idomeneo, an epic tale of a tortured Homeric-era hero trapped in a pitiless web of toxic fate, myth demythologized, would blaze the way to the surging dramatic expressiveness of the Romantic Age. This would be the opera that was not only to secure Mozart’s reputation for unrivalled inventiveness but one that was also to centre his theatrical star in the realm of abiding humanity and compassion.

Exiting its long-time home at Toronto’s historic Elgin & Winter Garden Centre, Opera Atelier makes a short trek two blocks north, unleashing a gloriously tempestuous revival of its epic 2008 production of Idomeneo at the handsome 1800-seat Ed Mirvish Theatre. Directed by Marshall Pynkoski, choreography by Jeannette Lajeunesse Zingg, the sizzling, high voltage energy levels of singer actors and dancers raise an already blustery piece to superstorm strength.

Plucked from relative obscurity, Idomeneo’s earlier, neo-classical French origins as a lesser known tragédie lyrique are all but indiscernible in Mozart’s compelling Enlightenment parable. Eternally frustrated by Salzburg-based librettist Giambattista Varesco’s awkward attempts to update the archetypal, vaguely Biblical tale of a long-ago king compelled by an omnipotent power to slay his own son, Mozart largely fashioned his own contemporary perspective on a brutal and brutish moral dilemma. Any enduring suggestion of fate as an inescapable force of nature was stripped away. Humankind is not born into dumb servitude, Mozart declared. The once venerable philosophical underpinnings of opera seria had lost all strength of purpose. The Age of Reason had grown to maturity and with it belief in the natural right of individuals to control their own destiny. Rationalism not superstition would guide our existence. Benevolence and selflessness would inevitably yield the greatest good.

The authenticity of stage expression so vibrantly on display throughout the course of OA’s hypercharged production is a vivid reflection of Pynkoski’s appreciation, not only of intricate Baroque idiom but more importantly, human values as mirrored then and now. Characters in this luminous Idomeneo, bold lighting design by Jennifer Lennon, soaring sets by Gerard Gauci, are sweepingly embodied.

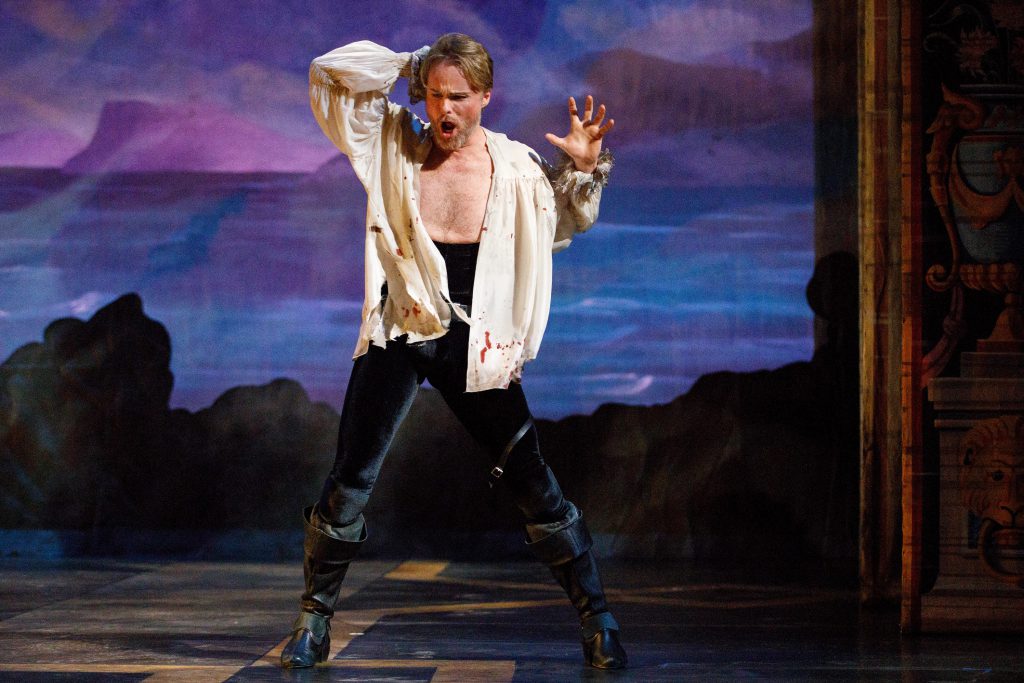

Idomeneo, king of Crete, returning champion of the Trojan War shipwrecked by Neptune on his own shore, symbolizes to a marked degree the prototypical monarch of the late Baroque. Assaulted by waves of changing fortune, Idomeno desperately struggles to steer the ship of state into calmer waters. The sun has set on his generation of rulers. Head in hands or in frantic flight from himself, tenor Colin Ainsworth inhabits the battered ex-warrior’s agony, a once great hero torn between surrender and resistance, tendering a performance of enormous drama and pathos. Fuor del mar ho un mar in seno/Che del primo è più funesto (“Torn from the sea, I have a raging sea more fearsome than before in my bosom”), he rails to the heavens, a tremulous, anguished cry ringing with coloratura.

Idomeneo’s son, Idamante, a chance sacrificial target as ordained by a wrathful god, partnered by Ilia, the captured Trojan princess who loves and is loved by him, together represent the new order. After a cruel interminable war, the kingdom of Crete craves peace. The heir-in-waiting and bride-to-be are the people’s best hope for a new order, a quintessential Baroque power couple, tolerant, free-thinking, mindful of abuses of authority. Appearing in respective roles, mezzo-soprano Wallis Giunta and soprano Meghan Lindsay fill the stage with emotion, Giunta forceful and focused. Singing Ilia’s poignant Act II aria, Se il padre perdei,/La patria, il riposo (“If I have lost my father, my country and my peace of mind”), a deep expression of profound loss laden with subtext, Lindsay enthralls.

If Ilia is the embodiment of human dignity and strength, Elettra, obsessed undeclared lover of Idamante, is raw passion personified. Menacing, traumatized, dangerous, the fugitive accomplice to a legendary murder, backstory assumed, signals an urgent warning to Mozart’s audience. And to us. The inevitable destructiveness of self-interest is graphically underlined. Commanding undying attention on stage from first entrance to final exit, soprano Measha Brueggergosman astonishes, gifting us with an Elettra of explosive dynamism. Her mad scene, blazingly headlined by Mozart’s incendiary Act III vengeance aria, D’Oreste, d’Ajace/Ho in seno i tormenti (“Within my breast I feel the torments of Orestes and of Ajax”) strikes straight to the core of monomania.

The impulse to draw parallels between the mythic world of Idomeneo — a son yearning for fatherly approval, Ilia’s struggle to retain her identity, Elettra’s spurned passion — and Mozart’s personal reality as a still youthful adult is irresistible. But the opera, incredibly his thirteenth at the time of writing, is far more than veiled autobiography. Empathy is surely more inducement to musical greatness than principal source of compositional power here. Mozart’s score radiates unique genius, a brilliant showcase for an endless succession of dazzling solos, accompanied recits and supremely inventive ensembles. Orchestral colours are shimmering, harmonies exquisitely filigreed. The music is, quite simply, stunning.

Playing with rich warmth and sensibility, Tafelmusik Baroque Orchestra, deftly led by conductor David Fallis, floods the Mirvish with immense beauty and excitement. Chorus master Daniel Taylor assembles a fine collection of fresh young voices, universal observers and commentators, by way of glowing choral backdrop.

Liberated from Salzburg, Mozart’s powers of creation intensified. Downtime awaiting new pages of libretto to arrive from home provided an opportunity to pen ballet accompaniment that mercifully required no collaboration with Varesco. Posts were slow. Over 20-minutes of sheer, joyful, unexpurgated music emerged. Lajeunesse Zingg celebrates every delightful second, plunging us into a glorious world of spectacle. Artists of Atelier Ballet dazzle.

As, indeed, does this entire show. A thundering theatrical triumph.

* * *

Above: Colin Ainsworth as Idomeneo. Photo by Bruce Zinger