To turn of the century opera audiences, she was Louise. To readers of latter-day French romance, her name was Mimi Pinson. One was the focus of a hugely successful stage work set in contemporary Paris, the other, the heroine of an enduring bestseller, but for all intents and purposes, the two characters were one and the same.

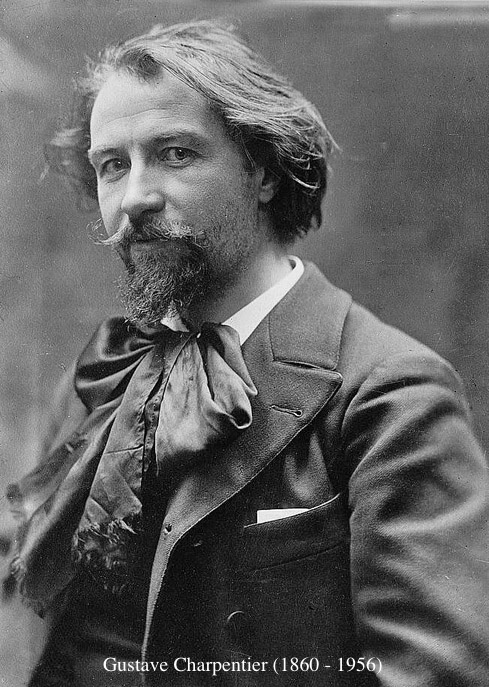

Gustave Charpentier, composer, activist, utopian dreamer, premiered his vivid lyrical drama, a gritty portrait of a youthful seamstress and her bohemian lover, in 1900 at the popular Opéra-Comique. Sultry, sharp, flashed with emotion, Louise swept Paris like a sudden storm. Recasting the heroine of a sensational novella by Alfred de Musset, Mademoiselle Mimi Pinson: Profil de grisette, Charpentier’s runaway hit cast the full spotlight of public attention on an entire urban underclass. Untold numbers of young working women, grisettes, had been forced into poorly paid, low status employment during the Third Republic, victims of class prejudice and a lack of educational opportunities. In a remarkable expression of art reshaping life, Charpentier diverted much of the considerable profit from his blockbuster opera to fund the creation of the Conservatoire Populaire Mimi Pinson, a professional music school providing free tuition to over 2000 disadvantaged shopgirls and garment workers. For a few precious hours each week, the Mimi Pinsons were taught to play parlour instruments and gathered to sing and dance, often performing in factories. Gradually, as the modern age acquired momentum, all Paris began to applaud them. Louise had done more than simply reflect the clash of budding socialist idealism vs. hostile status quo. Charpentier and his iconic heroine were among the first free-thinkers to proclaim the cause of women’s emancipation during the Belle Epoque.

On a sunny Sunday afternoon with a trace of winter still lingering in the chilly March air, Voicebox: Opera in Concert added its voice to Charpentier’s supporters in a theatrically deconstructed, vocally intense Louise sketched in broad crisp strokes. Directed by Artistic Director Guillermo Silva-Marin, powerfully energized by Music Director/Pianist Peter Tiefenbach, Charpentier’s dynamic panorama of love, longing and rebellion, was given a much welcomed hearing. Celebrated with over 1000 performances during its composer’s lifetime, by mid century Louise had fallen into virtual obscurity. Showcasing the latest in an ever-lengthening string of Toronto premieres, Opera in Concert proved that, despite decades of neglect, this opera is no quaint anachronism.

Written in an age of enormous change, Charpentier’s self-professed roman musical (“musical novel”) brought a sense of urgency and a universality of theme to an unapologetically melodramatic tale. The libretto, largely self-penned with occasional added flourishes by avant-garde poet Saint-Pol-Roux, mixes verismo frankness with brazen sentimentality.

Louise, a respectable dressmaker’s assistant, living with her parents in a shabby district of Paris, has lost her heart to her dashing neighbour, an artist, Julien. Louise’s mother violently disapproves of their frequent rendezvous. One day, she and Louise argue. Louise’s father arrives home from work, bone-tired after a long day of backbreaking labour. Slumped at the dinner table, he learns that Julien has proposed marriage to his precious daughter. The Mother, frustrated by her husband’s muted conciliatory tone, explodes with anger. Weary and defeated, Louise’s father asks Louise to read the evening paper to him. At news of preparations for spring in the city, Louise’s heart soars.

As morning breaks over Montmartre, Julien appears outside the atelier where Louise is employed, intent on spiriting her away. At first, Louise is overcome with confusion, torn between her loyalty to her parents and her love for Julien. The other seamstresses, gossipy and more than a little jealous, can only dream of ever experiencing a similar blossoming romance. After listening to a prolonged round of silly chatter, Louise hears the strains of a gentle serenade wafting into the workshop. It is Julien. Feigning illness, she rushes off to be with him.

Time passes. Louise and Julien have set up housekeeping in a humble cottage overlooking the city. Liberated from her parents’ control, Louise’s life is filled with joy. Neither she nor her carefree lover have need of wedlock to seal their union. A band of their bohemian friends assembles and playfully crowns Louise Muse of Montmartre. Suddenly, her mother enters. The revelers slink away. Louise’s father, heartbroken at his daughter’s desertion, has lost the will to live. Louise is devastated. Her mother begs her to comfort him. Neither will stand in her way of returning to Julien’s arms once the Father is well. Mother and daughter depart.

One evening later that summer, rejuvenated by his daughter’s presence, Louise’s father reflects on poverty and the pain of losing a child. He has become an embittered man. Despite her earlier promise, the Mother forbids her daughter to resume her sinful relationship with Julien. Longing for happier times, Louise’s father recalls the lullaby he once sang to his little girl. Louise feels suffocated and emotionally pulls even further away. Louise’s father loses patience and orders her from the house. Louise flees. “Louise! Louise!” Her father’s frantic change of heart comes too late. Louise has vanished into the gathering darkness. “Paris!”, he rages, cursing the City of Light.

The legacy of Charpentier’s bohemian student days in Paris frames essentially all the flamboyant features adorning this supercharged saga. The City of Light is forever centre stage, electrifying and alluring, heedless and dangerous. Characters are not so much accented by the setting, more a consequence of it. From the shabbiness of Louise’s home emerges her bitter, worn out parents. A menagerie of shady derelicts, Errand Girl, Rag-Picker, Night-Prowler, all sadly lost to timing cuts in an otherwise generous Voicebox offering, springs from the shadowy streets. Louise is an opera built not so much on traditional acts, more on loosely linked tableaux, each and every one traversed by the same, solitary figure, a young woman eternally alone in the crowds.

The human quest for identity and independence, love and acceptance, respect and self-worth defines Louise’s passage to maturity. It needs little in the way of imagination to read Charpentier’s coming-of-age story as part of a much larger narrative. Louise endures because, as Opera in Concert’s intimate presentation made quite clear, Louise is a mirror reflection of ourselves, once and always.

Charpentier’s exquisite, richly textured music is no less compelling. Tutored by Massenet at the Conservatoire de Paris, the classically trained young composer launched his professional career with an abiding affection for 19th century forms. The eloquent tropes of French Grand Opera pour from virtually every bar of Louise, scrupulously tonal, punctuated with an occasional chromatic sting. Charpentier revered Romanticism but he was at heart a revolutionary and the range of tints in his vibrant music foreshadows bold changes to come. Maestro Tiefenbach stirringly invoked not only the abundant tenderness of the score, but also its bursts of edginess, repeatedly punching open a piano score that refused to lie flat, an accidental metaphor but still wonderful punctuation.

Inhabiting the title role of Louise, soprano Leslie Ann Bradley gave a performance of sweeping virtuosity and radiance. Her sparkle and brightness dazzled, her mid to lower range open-hearted and warm. Bradley is an elegant artist gifted with a fluid instrument wielded with great assurance and superb technique. Her show stopping rendition of Charpentier’s magnificent Depuis le jour (“Since the day”), frequently extracted as a stand alone concert aria, was quite simply gorgeous.

As Julien, tenor Keith Klassen struggled with the host of taxing demands imposed on the character by the composer. The tessitura for Louise is punishing, relentlessly high and unforgiving. The emotive and physical challenges facing a performer playing the opera’s resident lover/free-spirit/rebel are no less considerable. Regrettably, try as he might, Klassen frequently stumbled as he attempted to clear the daunting dramatic and musical hurdles in his path.

Singing with great lustre, mezzo Michèle Bogdanowicz brought a haunting sense of vulnerability to Louise’s Mother, endowing her combustible character with a fathomless depth of shattered humanity. Scarred, bitter, helpless, this was a woman lost to life, isolated, beyond reach. The ferocity of raw emotion unleashed by this sensitive singer actor was as heartbreaking as it was terrifying.

Baritone Dion Mazerolle appeared as Louise’s Father, vocally resonant and assertive, dramatically commanding. His character’s starkly defined passage from contentment and resignation to spite, rage and savagery over the course of two utterly detached acts required supreme concentration and nimble artistic instincts. Mazerolle astonished, setting Act IV ablaze with fury, then quickly extinguishing the flames, abruptly seguing to the stillness and quietude of Reste… repose-toi (“Stay here… stay and rest”). Time froze. Mazerolle mesmerized.

The Voicebox Chorus did multiple duty, members singing as both a comprimari-rich cast of street people, dress-makers and denizens of Montmartre, as well as executing their rousing assignments as choristers. Characterizations and drama flowed freely.

A decade after Louise premiered, Charpentier introduced the world to a sequel. Julien transported the young couple to Rome where they continue to live the bohemian life, literally lost in their dreams. Audiences in Paris and New York greeted the new work with spectacular indifference. Julien closed after two performances. Charpentier never wrote another opera. He died at the age of 96.

Louise was and is a phenomenon, its composer, a distracted genius. With its final presentation of 2014/2015, Voicebox: Opera in Concert gave Toronto a rare glimpse into the lives of two unique individuals, a grisette songstress and the bohemian composer who made her famous. It was a privilege to meet them.