Claudio Monteverdi’s commitment to opera, once encountered, never truly out of mind as time would prove, was to form the keystone of his overarching legacy, testament to the composer’s personal and professional courage in the face of cruel pain and loss.

Charged at the midpoint of his career by his then employer, Vincenzo I, Duke of Gonzaga in Mantua, to write a suitably grand scena rappresentativa in the increasingly fashionable musical story-telling style, Monteverdi essentially discarded the prevailing pattern book. A working musician more inclined to catchy madrigals than the faddish intellectual notion of sung drama as derived from chanted Greek tragedy, the seasoned native Lombard songsmith emerged from his study with what amounted to a radically reformed vocal art form. Narratively driven, emotionally raw, his favola in musica (musical fable), L’Orfeo, caused a sensation among Mantuan nobles and local insiders alike when it premiered at the ducal palace during Carnivale in February, 1607. Suddenly, three months later, Monteverdi’s wife died of unknown causes, followed in short succession by the death of his 18-year old ward, a promising young soprano, struck down by smallpox.

Devastated and depressed, Monteverdi retreated to his home town of Cremona, his follow-up theatrical triumph, L’Arianna, buried in his grief. Ultimately settling in Venice, the shattered composer assumed a more discreet existence as maestro di cappella at La Serenissima’s hallowed Basilica di San Marco. He would not venture into the opera world again for over 30 years but when at last he did at the age of 73, his last two masterpieces, Il ritorno d’Ulisse in patria (The Return of Ulysses) and L’incoronazione di Poppea (The Coronation of Poppea) would mesmerize an entirely new brand of audience. Opera was rapidly gathering middle class, ticket-buying momentum and Monteverdi, who would forever deny he was in the slightest revolutionary, once again found himself leading a renewed attack on the musical status quo.

Taking his final bows as resident Artistic Director with the Toronto Consort late last week, conductor David Fallis, accompanied by a vibrant cohort of period specialists, singers and players, returned us to Monteverdi’s operatic roots with a shimmering concert presentation of the trailblazing early 17th century maestro’s landmark Orfeo. A glowing reflection of the touching myth of lovers all too briefly reunited beyond death, Trinty-St. Paul’s Centre rang with all the brilliance and passion of a tremulous age.

Orfeo’s taut compositional architecture, built on a regular framework of expressive solos and the occasional intimate duet interspersed with recurring choral commentary, gives rise to a scrupulously formal structure. The seesaw between polyphony and monody, intricate multiple-voiced harmony vs. crisp stand-alone declamation, is almost mathematical in its symmetry. Monteverdi essentially builds his Baroque fairytale opera atop older forms leaving more than a few recognizable features, no doubt deliberately, by way of reference points. Arias emerge from popular ballads. Madrigals echo through choruses. The ordered universe of the Renaissance has not yet quite been disassembled.

The stirring toccata that opens Orfeo, splendidly played on a deliciously summery spring evening by members of Montreal’s La Rose des Vents, might very well have been written by Monteverdi’s 16th century predecessor at San Marco, Giovanni Gabrielli, cornetto and sackbuts summoning us to mass. But this is neither reverential nor pastiche. The use of brass in what amounts to the equivalent of a courtly pantomime would have been startling to Monteverdi’s Mantuan onlookers. The variety and vastness of orchestral forces employed by the composer propel his first unqualified operatic hit into the realm of daring experiment. Totalling some two dozen players with expanded continuo section — twin theorbos, two organs plus harpsichord and triple harp — Fallis and company offered a vivid demonstration of Monteverdi’s genius for evoking seemingly boundless panoramas of vivid instrumental colour.

Revealing a similar historic talent for counterpointing the familiar with the new, librettist Alessandro Striggio, a clever young lawyer and enthusiastic amateur violist, begins his fraught narrative in what would have been comfortable pastoral territory in his day reminiscent of Virgil’s Eclogues. What follows, however, is a wholesale shift in tone and setting. News of Orpheus’s beloved Euridice’s death sweeps us into the darkness of an Underworld brimming with tense psychic menace. The heavenly and the hellish, the realm of eternal harmony overseen by Apollo who summons Orpheus to the starry heavens and Pluto’s infernal dominion of suffering and torment, battle for ascendancy in drama and music. Hints of dissonance haunt Monteverdi’s unfailingly evocative score. A variety of highly prismatic voice types graphically embodies character and mood, a distinct, overtly theatrical device arguably never invoked to better effect before.

Singing the title role in this sensitively observed Orfeo, visiting English tenor, Baroque virtuoso Charles Daniels sang with immense passion and unexcelled grace, charming and anguished in equal turn, his voice mirroring all the joy and exuberance, sorrow and despair of Monteverdi’s profoundly moving music. Possente spirito (“Mighty spirit and fearsome deity”), the composer’s celebrated aria, a virtual Mt. Olympus of trills and roulades voiced with generously proportioned coloratura cast an achingly beautiful spell.

Glimpsed in a double role, as is so often the case with singers spotlit in expansive concert environments, Katherine Hill set the stage with a lovely, lyrical turn as the eponymous muse, La Musica, followed engagingly, albeit briefly in Monteverdi’s retelling of the Orpheus tale, as Euridice.

Mezzo-soprano Laura Pudwell was the Messenger, Silvia, also appearing as Speranza, embodiment of Hope, the first bearing news to Orfeo of Euridice’s death, the second, an offer of hope for reunion with his beloved in the Underworld. No stranger to early opera, Pudwell brought great authority to her recits, exposition forcefully and masterfully expounded.

Michele DeBoer was a delightful Ninfa the nymph, appearing in more definitive guise as a warm-hearted Proserpina. Baritone David Roth was a commanding Pluto. Bass-baritone John Pepper was a rumbly Caronte, prickly boatman of the Dead. Kevin Skelton was a divine Apollo.

All artists ultimately sang as choristers, one voice per part as Monteverdi demands. Act II’s mournful assembly of grieving nymphs and shepherds with its embedded, highly affective mini-ensembles was particularly fine.

Irrepressible dance themes, dynamic orchestral interludes, lingering motifs, Orfeo explodes with energy. The Toronto Consort played with glorious animation and refinement. 27 years with Maestro Fallis concludes on a ringing, exultant high note.

* * *

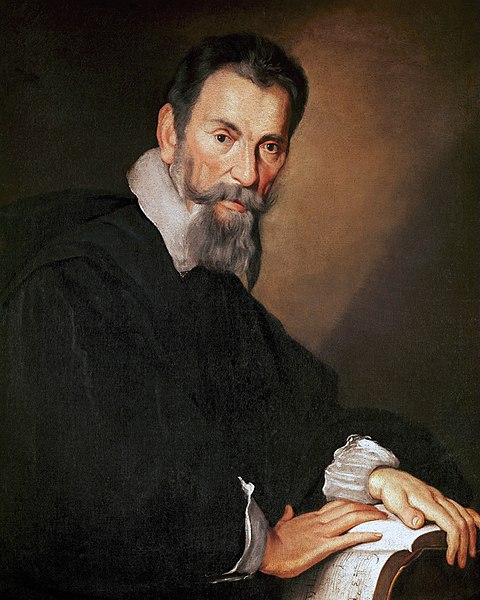

Above: Claudio Monteverdi by Bernardo Strozzi, c. 1630. Tiroler Landesmuseum, Innsbruck