By 1738, George Frideric Handel’s booming West End stage machine was losing traction. The London appetite for Italian opera seria, a craving he had almost single-handedly satisfied for nearly forty years, had dulled. His revenues were in freefall. A rival company, the once robust Opera of the Nobility, had already failed. A new oratorio, Handel wagered, might be just the ticket to satisfy his audience’s taste for less highbrow, more populist entertainment. Earlier excursions into the form had earned him considerable notice.

Friend and collaborator Charles Jennens, amateur librettist and full-time eccentric, sparked Handel to fresh greatness. Saul, the pair’s intensely focused, highly charged portrait of the vindictive Old Testament king, debuted to thunderous applause. Handel had the smash hit he so desperately needed. His next venture with Jennens would be Messiah.

The English oratorio had come of age.

Tafelmusik, Canada’s premier Baroque orchestra and chorus, brings a new Saul to Toronto’s Koerner Hall laced with drama presented on an ambitious musical scale. Conductor Ivars Taurins leads his ample cohort of musicians and singers to the summit of Handel’s monumentally expressive score. A concert performance minus even the most modest stagecraft rarely has more sweep.

Adapted from the First Book of Samuel, Saul’s libretto makes sense of the original patchy Biblical saga, here clarified and extended in a decidedly original remoulding. With Jennens’ pronounced flair for the theatrical, the mad Israelite king’s narrative is transformed into a tense, psychologically textured three act arc.

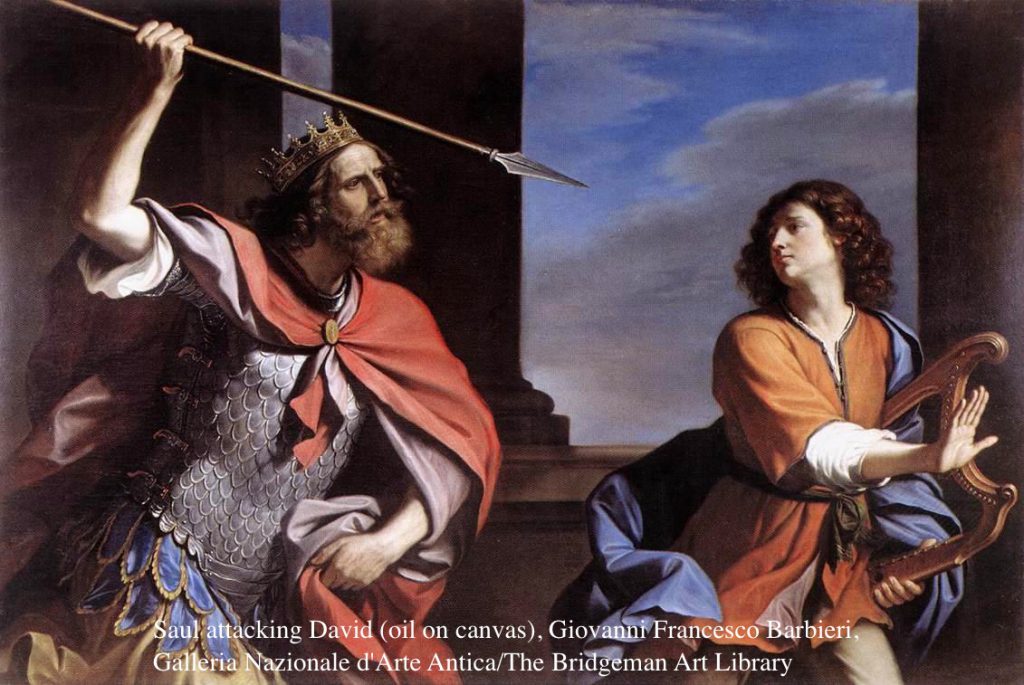

The Israelites are jubilant. The young warrior, David, has slain Goliath, their Philistine enemy’s champion. King Saul, in gratitude, pledges his eldest daughter Merab’s hand in marriage. Merab is offended. David is of low born stock while she is a noble princess. The Israelite women gather to sing their new hero’s praises, provoking Saul to ferocious jealousy. His younger daughter, Michal, secretly in love with David, urges him to quell her father’s fury with his harp but Saul cannot contain himself and hurls his spear at David. Miraculously, his intended victim escapes unharmed. Saul orders his son Jonathan to pursue and kill him.

The Israelites lament their king’s sinful envy. Jonathan resists Saul’s murderous decree. Assuring David of his devotion, he reveals that his father has married Merab to another. David is untroubled. He has fallen in love with Michal. Jonathan intercedes with the king on David’s behalf, reminding Saul of his faithful friend’s valour. Saul seemingly relents and dispatches David to lead his army against a renewed Philistine threat, privately hoping that the youth will lose his life. But David is triumphant and, returning to the Israelite court, reveals that Saul, spear in hand, has tried to slay him a second time. Michal and Merab are horrified. Their father’s savagery knows no bounds. Jonathan, too, becomes Saul’s target when he dares to defend David yet again.

Saul, despairing of his own self-ruin, seeks a mystic, the Witch of Endor, to summon the spirit of the Prophet Samuel to counsel him. The ancient sage foresees nothing but doom. Saul and Jonathan both will perish at the hands of the Philistines. And so it comes to pass. Saul, Jonathan, the kingdom, all are lost. The Israelites gather to mourn. David, too, is stricken with grief. “O Jonathan!”, he laments. Still the Israelite people live in hope. David, God’s anointed, will be their new king. His righteousness and courage will restore their fallen nation to glory.

In many ways, Saul marks a fresh start for Handel. Although arguably the most opera-like of all his oratorios given its intensity, this first of his truly great musical Bible stories represents yet another stage in the composer’s endlessly adaptable career. The solemnity of Saul’s subject matter and its familiarity to audiences of the time required a more grounded musical vocabulary than Handel had used to tell his flamboyant operatic tales. More straightforward expressions of emotion, pure and unadorned, at least to eighteenth century ears, were to be Handel’s new normal for oratorio. Strong, recognizable characters. Streams of heartfelt English recitative. Accessible entertainment, certainly, but far from humble. George Frederic was not one to be stingy when it came to pleasing his fans.

Saul’s orchestration is outrageously grand demanding a generous number of players and variety of instruments, all splendidly represented in Tafelmusik’s finely tuned historically informed presentation. Period trombones, allegedly used by Handel to imitate the sound of the shofar, fronted by a phalanx of Baroque oboes and bassoons provide a vibrant depth of colour. A keyed carillon yields chiming bell effects; a chamber organ, a sombre, swelling tone; harp, a celestial solo; kettledrum heroic, heart-pounding percussion. A sixteen member string section, including a pair of double basses combined with two natural trumpets rounds out the inventory of vivid sound. This is music designed to appeal and Tafelmusik delivers with skill and assurance, softly sorrowful in Saul’s famous Dead March, rousing in the oratorio’s numerous symphonic interludes.

Singing Saul’s title character, baritone Peter Harvey presents us with a dark, glowering Israelite king, dangerous and deranged. Although relatively light in timbre, Harvey’s sound is deeply assertive. Liquid and wide-ranging in his vocal reach with a definite high note-friendly quality, the British Baroque specialist brings both flexibility and appealing solidity to his singing. Saul’s mighty aria overflowing with malice and spite for Jonathan, “Serpent in my bosom warm’d” is delivered here with robust, reverberant coloratura to chilling effect.

Countertenor Daniel Taylor gives a subtle, sensitive performance as David, his tone clear and multi-hued. There is tenderness and charm in this luminous, ethereal voice. Spirit and sensuality, too. With his abundance of transparent technique and charismatic presence, Taylor projects a tangible humanity on stage, his style vital and unforced. Handel’s David is dawn to Saul’s darkness. Taylor’s singing is radiant.

Sopranos Joanne Lum and Sherezade Panthaki are sisters Merab and Michal respectively. Both are excellent. Merab’s haughty reaction to the notion of marrying David, “My soul rejects the thought with scorn”, as sung by Lum is as sharply characterized as it is superbly declaimed. Panthaki’s somewhat lower pitch and earthier colours serve her well throughout the demanding range of her many acutely impassioned appearances. Michal is the respectful, obedient daughter in Saul’s household, well defined here by style and vocal quality. Rich, warm and full, Panthaki’s sound seems to grow even stronger with each new accompanied recitative and aria she encounters on her character’s journey to maturity.

Rufus Müller’s smooth, gleaming tenor is well-suited to his role as Jonathan. His stormy Act I exchange with Paul Harvey’s Saul, both voices dynamically opposed, is an explosive encounter ablaze with some of the night’s most dazzling singing. Act II moments with Daniel Taylor’s David are infinitely gentler and more solicitous but no less engaging. Jonathan is not a vast part but it is packed with expression. Müller’s realization is a model interpretation.

Saul’s chorus plays an active part in its own right in Handel’s great oratorio, shaping key moments in the story. Assembled as joyful Israelite women, sopranos and altos raise their anthem of praise for David. Mourning the loss of king and country, the full chorus, cast as the Israelite nation, lends voice to a heartrending funeral service. Singing as both a congregation of participants as well as commentators, the Tafelmusik Chamber Choir triumphs, turning in a glorious performance of enormous vibrancy and vocal animation.

Handel would compose another eighteen oratorios in the wake of Saul’s premiere, some as popular, some less so. Few were ever more successful artistically. Handel’s stark tragedy is unquestionably a masterwork. Tafelmusik has delivered a fine, polished rendition, one that deserves to be preserved in more than memory. We can only hope that it will soon be recorded.