Intellectually consumed, endlessly entangled in theories of art and existence, Richard Wagner was never one to deny himself the singular satisfaction of slapping authority squarely in the face.

While untypically employed in a lucrative establishment position in 1849 as Hofkapellmeister at the royal theatre in Dresden, Wagner bristled at his perceived confinement on the fringes of the Saxon court. In May he took to the barricades as an enthusiastic pamphleteer in support of a fervid band of revolutionaries, among them Russian anarchist and friend Mikhail Bakunin, all determined to overthrow the local antique monarchy. The state struck back hard, crushing the rebellion in a matter of days. Wagner fled, an arrest warrant for treason, a capital crime punishable by death hanging over his head, settling in nonpartisan Zurich with wife Minna.

The following decade spent in exile would be a period of acute creative fervour for Wagner. New operas crowded his mind, the first a largely self-invented mythic tale of a Nordic warrior raging against the gods, a defier of fate, a valiant upholder of free will. Begun in 1851 as Der junge Siegfried (Young Siegfried), Wagner’s initial story sketch quickly grew, almost organically, into an epic 4-part prose poem. Bookended by an episode of backstory and a concluding instalment focused on his hero’s death, Der Ring des Nibelungen (The Ring of the Nibelung) sprang as much from the composer’s determination to consign the status quo to extinction as it did from his resolve to create a distinctly German form of music drama.

Siegfried was to be a proclamation, a ringing call to battle in the struggle to establish the new social order to come. First performed 140 years ago at the purpose-built Festspielhaus in Bayreuth, Wagner’s immense, 5-hour celebration of the cult of the individual represents not only a breakthrough in operatic form and expression, but a harrowing revelation of one of Wagner’s darkest ideals.

Premiered in Toronto in 2005, revived in 2006 as part of late general director Richard Bradshaw’s inaugural Ring cycle at the city’s then newly opened Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts, the Canadian Opera Company revisits the past with a savage, disturbingly inward-looking Siegfried. Faithfully retracing the production’s postmodernist journey to the centre of human obsession, director François Girard’s eerie, psychotic dreamscape survives in untampered form, an enduring troubling and troubled hallucination.

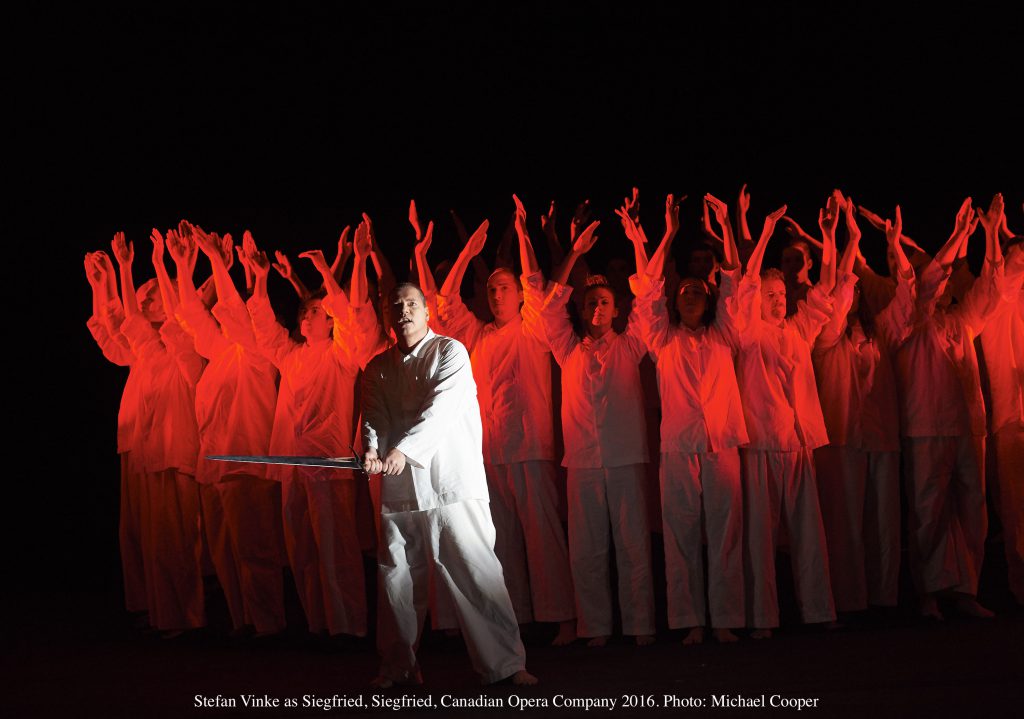

Dressed in crisp white pyjamas, as is virtually every member of Girard’s ensemble in blunt artistic overstatement, singer actor Stefan Vinke’s Siegfried commands centre stage, an instant target of attention at curtain rise. Seated on a sheared tree trunk, a quasi thought bubble stuffed with the detritus of his chaotic world poised above his head — a ruined temple, dangling corpses, floating ghosts — Wagner’s brooding superhero promptly asserts his presence. Death is literally in the air.

Moral niceties are to be ignored in this remorseless realm. Fafner, giant turned dragon, guardian of the legendary omnipotent golden ring is slain by Siegfried more to test the limits of his fearlessness than to claim the precious treasure. Mime, the grasping Nibelung blacksmith who raised Siegfried, a demi mortal Wälsung waif, is slaughtered simply because he irritates the hulking sword-wielding adventurer. The future, as Wagner loudly proclaims, belongs to the man of action, he who has no conscience, a brutally efficient, unthinking killing machine. It is a mad, fevered vision, hideously distorted. Our only refuge, at least in director Girard’s rendering, lies in the fact that Siegfried’s shadowy, nightmarish universe lit with the occasional flash of dazzling beauty necessarily implies an eventual awakening. Wagner’s hero, like his warrior heroine Brünnhilde, will surely shrug off sleep. Reality will be restored. But there is a problem.

If all that transpires on stage is slumber-induced fantasy then the power of Wagner’s intricately constructed myth and ultimately our need as an audience to accept it is called into serious question. Embed Siegfried in the realm of dreams and the story is emptied of consequence. The narrative arc goes flat. The opera not only loses meaning and implication, it can logically have no sequel. The Ring saga can not advance because Siegfried never happened. The lack of resonance here is curious.

There is, however, nothing even vaguely inconsistent about the quality of singing on offer here. Vinke’s Siegfried fills the FSC’s ample auditorium to overflowing with rolling waves of sound. Although somewhat monochromatic, lacking a touch of sheen on occasion, this is a commanding Wagnerian lead, a guileless force of nature, muscular, uncomplicated, explosive. Lending compelling vocal weight to the production’s highly abstract staging of Siegfried’s cacophonous forge song, a circle of waving, disembodied arms bodily metaphors for a pitful of lapping flames, Vinke’s robust heldentenor sets the scene ablaze.

Appearing as Mime, Wolfgang Ablinger-Sperrhacke reaches deep into the psyche of Siegfried’s grubby guardian, extracting a breadth of characterization seldom associated with the luckless little Nibelung. Weary, disillusioned, abused, the scurrying mud-streaked creature arouses genuine pathos. Gifted with an unerring smoothness of line and flexible timbre, Ablinger-Sperrhacke’s lighter, speech-inflected tenor enchants, arguably nowhere more entertaining than in Mime’s blatantly disingenuous Act II exchange with Siegfried, his true intention to poison him and snatch the ring laughably revealed.

As The Wanderer, Alan Held enthralls, his bottomless bass-baritone magnificently voicing the once mighty god now in decline, thundering and raging, piano and pitiful. A more moving rendition of Wotan’s heartfelt surrender to bitter fate, Wait’ itch in wütendem Ekel des Nibelungen Neid schon die Welt (“Though in fury and loathing I flung the world to the Nibelung’s envy”) is, in all likelihood, not to be found.

Singing the role of Brünnhilde, Christine Goerke is, quite simply, glorious. Aroused from enchanted sleep by Siegfried’s kiss, Wotan’s cherished daughter is resurrected from the protective ring of magic fire, her final resting place in Die Walküre, to the world of deeds. Heil dir, Sonne! Heil dir, Licht (“Hail to thee, sun! Hail to thee, light!”), she rejoices igniting one of opera’s greatest love duets, a lush, sprawling declaration of tenderness and warmth, passion and desire. Goerke is extraordinary, her brilliant, far-reaching soprano sparkling with entire spectrums of colour, breezily soaring above a towering 112-player COC Orchestra. It is a stunning moment, without question the highlight of the night.

Baritone Christopher Purves sings a ferocious, snarling Alberich. Bass Phillip Ens voices a growling, resonant Fafner off stage. Jacqueline Woodley is the Forest Bird, a delightful, fluttery apparition with a lovely bright soprano to match. Contralto Meredith Arwady is an astonishing Erda, the earth goddess, her rich, fertile sound glowing with life.

The Canadian Opera Company Orchestra stirringly conducted by resident music director Johannes Debus performs Wagner’s sumptuous, supremely romantic score with great sweep and verve, precisely charting every measure of the composer’s fabled chromaticism.

Siegfried is not an easy opera from any point of view. Demanding and taxing for performers and audience alike, the work stands as an excruciatingly intense evocation of gesamtkuntswerk, Wagner’s longed for synthesis of theatre, music, poetry and art. Ultimately, the frustrated composer would abandon the goal, declaring it unachievable.

More bridge than stand alone masterpiece, a precarious path from the engaging dramaturgy of Das Rheingold and Die Walküre to the sharp characterizations of Götterdämmerung, Siegfried is unquestionably best enjoyed as part of the larger Ring continuum. Even given the abundance of exceptional music-making on stage and in the pit, the COC’s current production could happily benefit from the added legitimate support of surrounding episodes.