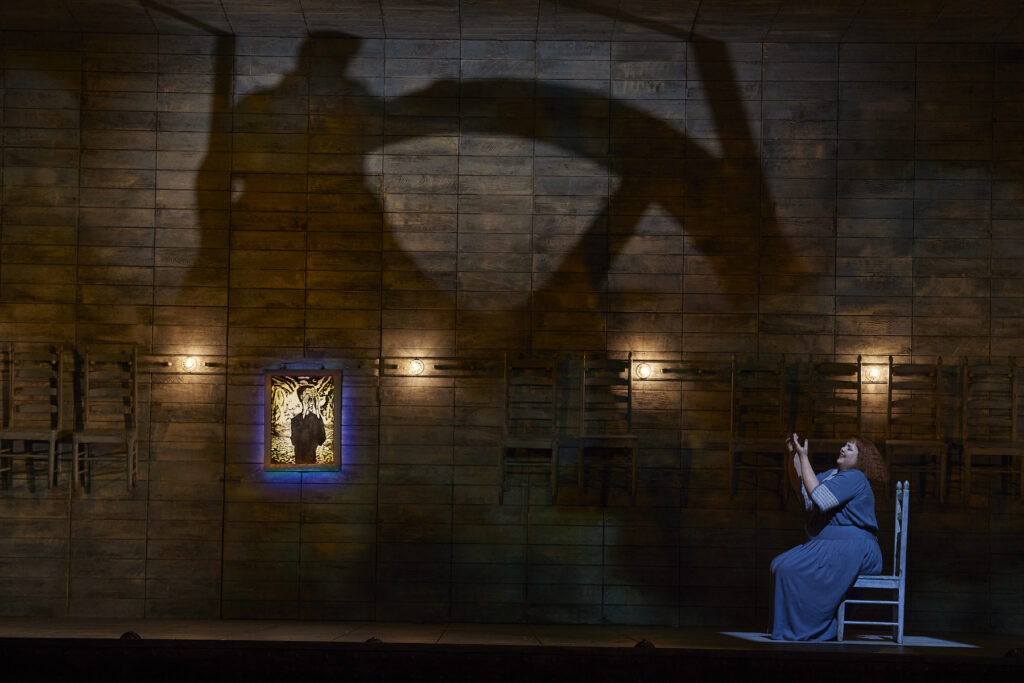

The image confronts us from the first moment we enter the theatre, a gaunt, hollow-eyed figure, hands raised to face in an attitude of horror and despair. The portrait, an eerie print projected onto the front of house drop, will be the focus of a good deal of our attention for some considerable time to come, appearing and re-appearing on stage, the object of increasingly frenzied dramatic obsession.

Mann in der Ebene (Man on a Plain), an unsettling monochromatic woodcut created in 1917 by the German expressionist, Erich Heckel, speaks — piercingly, graphically — of the age in which it was created, a remorseless, searingly violent period of cataclysmic war and explosive revolution. Anarchy is summoned. Chaos evoked. The opera builds to a raging climax, terrible in its inevitability. The end comes with the crack of a shotgun. Overarching catharsis is nowhere to be found.

First presented in 1996, remounted in 2000 and again in 2010, originating director Christopher Alden’s expressly modernist take on Wagner’s harrowing Der fliegende Holländer (The Flying Dutchman) storms into the Canadian Opera Company’s Four Seasons Centre, a 2022/23 season opener, as steadfastly brutal, blunt and controversial as the day it was launched.

Myth and legend loom large.

Wagner forever insisted that the inspiration for his tempestuous three-act Romantic saga, a haunted tale of a phantom vessel captained by a cursed adventurer and the woman who releases him from a devilish spell, was anchored in first-hand experience. Fleeing from restive creditors in 1839, he and wife Minna — who tragically suffered a miscarriage during their flight — hastily boarded a ship on the Baltic coast bound for London. Blown off course by a howling hurricane, the battered barque took refuge in a Norwegian fjord where Wagner first learned the ghostly legend from the crew.

Truth or myth-building? Wagner seized every opportunity in life to amplify his self-claimed status as operatic progenitor, author Heinrich Heine’s published version of the folktale in 1831 notwithstanding. Self-promotion aside, the composer’s claim has something of the ring of authenticity about it. A ferocious North Sea gale. Sailor-borne superstition. Fundamental realties inextricably embedded in story and score.

Seen from a feminist point of view, a vital perspective in the face of Wagner’s self-penned, testosterone-fueled libretto, story assumes much darker hues in Alden’s telling — a distinctly irreligious tale of epic moral collapse. This is very much Senta’s narrative, The Flying Dutchman’s landlocked, love-locked heroine, the Dutchman a mere catalyst to her hideous sacrifice in the name of quasi heroic masculine redemption. The wandering mariner’s ersatz portrait held before her like some precious icon, Senta advances towards her destiny, her death at the hands of a jealous suitor certain proof of her embrace of the godforsaken seafarer’s suffering, the key to his prophetic release from pain. God bless her, says Wagner. God save us from mankind, says Alden.

There is no saintly passage to heaven for this abused, forgotten angel. No glory. No salvation. To bear witness is excruciating. And disturbingly pointed.

Rapidly rising Metropolitan Opera discovery, Marjorie Owens, deeply inhabits the character, imbuing her performance with almost equal measures of dignity and monomania , guilessness and biting resolve, her towering dramatic soprano an inexhaustible force sweeping aside any hint of reason or self-doubt on Senta’s part. To hear Owen‘s rendering of Senta’s impassioned aria, Traft ihr das Schiff im Meere an,/blutrot die Segel, schwarz der Mast? (“Have you met the ship at sea/with blood-red sails and black mast?”) — one of only a handful of extended, through-composed ballads in an opera strictly circumscribed by Wagner’s theory of gesamtkuntswerk — is to experience an artist of exceptional strength and deftness singing from the soul.

Appearing in the intensely moody pivotal role of the Dutchman, Johan Reuter, immensely impresses. Commanding, resonant, decidedly high note friendly, the widely acclaimed Danish bass-baritone delivers a poignant, supremely vulnerable Dutchman, partnering Owens in the potent Act III confrontation scene — Wie aus der Ferne längst vergangener Zeiten/spricht dieses Mädchens Bild zu mir (“As from the mists of times long ago/this girl’s image speaks to me”) — with a finely wrought declaration of abiding hope underscored by eternal damnation.

Singing with an abundance of presence, bass Franz-Josef Selig evokes mixed feelings as Daland, vigilant captain to his hard-drinking, unnervingly tankard-slamming, armband-wearing crew yet willing to sell his daughter, Senta, to the Dutchman in return for the doomed seaman’s treasure.

Fellow heldentenors Miles Mykkanen and Christopher Ventris are The Steersman and Erik, the huntsman, respectively. Mykkanen contributes an extraordinarily physical performance ringing with great dynamism and musicality. Ventris gifts us with a heartbreakingly tender rendition of Wagner’s anthem of love and loss voiced by the hapless heroine’s sweetheart, Senta, o Senta, leugnest du? (“Senta, oh Senta, you deny it?”).

In an affecting turn as Mary, a factory foreman in Senta’s remote, claustrophobic hometown, mezzo-soprano Rosie Aldridge delights, all business and bustle, contralto-like timbre rumbling beneath her spirited Act II scene.

Marshalled into two distinct cohorts, the men and women of the Canadian Opera Company Chorus utterly thrill; the men — Hojohe! Halloho! — rival crews of storm-tossed sailors, dead and alive; the women appearing as a raucous band of weavers. Frames banging, spindles flying, mime and music meet, chorus director Sandra Horst’s factory girls brilliantly animating designer Allen Moyer’s stark monoset, far more convincingly industrial than nautical in appearance.

Music director Johannes Debus conducts, leading the incomparable Canadian Opera Company Orchestra with a genuinely exhilarating evocation of Sturm und Drang. Dynamics and tempi receive special care. Harmonies are fluid, instrumental colours consistently bright. The overture, something of a 10-minute summming up of the entire Wagnerian orchestral aesthetic, is particularly well played.

Wagner was scarcely 30 when The Flying Dutchman was premiered. Much of the orchestration has the air of youthful experimentation, particularly evident in the composer’s enthusiasm for leitmotifs, a pioneering venture at the time. The Dutchman is heralded by a surge of brass, horns rolling over us in waves of expectation. Senta’s presence is announced by the softer wash of woodwinds, the gentle lap of innocence. It was in these moments that history was made.

The music is timeless.