Georges Bizet, composer of one of the world’s single most popular operas of all time, sadly lived and worked in the shadow of success for virtually his entire life. Carmen, by far his greatest hit, scarcely raised a ripple of attention when it premiered at the Opéra-Comique in Paris in March 1875. The Pearl Fishers (Les pêcheurs de perles), written twelve years earlier, caused even less of a stir at the box office. The critics were ruthless. “There were neither fishermen in the libretto nor pearls in the music,” sniffed Le Figaro. Bizet himself had reservations about the work’s enduring value despite the encouragement of several celebrated contemporaries. On June 3, 1875, Georges Bizet died of a sudden heart attack at the age of thirty-seven. The brilliant young talent with such promise so admired by Berlioz, Gounod and Saint-Saëns was never to know the greatness that time would bestow. Opera, for Bizet, was forever to be a struggle against nagging feelings of professional insecurity and self-doubt.

Opera Hamilton’s touching production of The Pearl Fishers movingly captures the tragic irony of an opera profoundly undervalued by history. With its stellar cast of fine young featured singer actors and its enthusiastic staging, a work long considered underwhelming by critics and musicologists alike, is given a much welcome revisit. The production challenges are great for the tenacious Hamilton company. The city’s 750-seat Dofasco Centre for the Arts is decidedly opera unfriendly. Orchestral sound is almost swallowed whole in the depths of its sub-stage pit. Direct line-of-sight contact between conductor and performers, essential for basic musical communication, is questionable. Technical resources are sparse. And yet, despite everything, an acoustically unforgiving venue, limited stagecraft, modest set, this irresistible, wholehearted production effectively triumphs on stage.

Somehow even the awkwardness of The Pearl Fishers’ much-maligned story is overcome.

A pair of pearl fishermen, friends parted since youth, are reunited on an exotic seashore. The first, Nadir, has returned from adventuring through dark inland jungles. The other, Zurga, has just been elected headman of a local fishing village. The two reminisce, recalling their mutual love for a beautiful Hindu priestess, a love each had forced himself to renounce in the name of friendship. No sooner have they pledged their undying loyalty to one another, when Léïla, devotee of Brahma, arrives to assume her new sacred duties at a nearby temple. Unbeknownst to Nadir and Zurga, her heavy ritual veil conceals the very priestess they had both once adored.

Nadir passes a sleepless night wrestling with his conscience. He has, in fact, returned to his native shore with the sole purpose of winning Léïla’s love. She, in turn, has been secretly awaiting him. The two are inevitably brought together to declare their enduring passion. Nourabad, the high priest, discovers the lovers locked in a fervid embrace. They must be executed for corrupting the faith, he thunders. Zurga rushes in to intervene. As leader of the fishermen, he alone will decide their fate. Furious, Nourabad tears aside Léïla’s veil. Zurga instantly recognizes the necklace she is wearing. It is the very one he once gave her when she was a girl in thanks for sheltering him from a band of murderers. Like his once faithful companion Nadir, he too has loved the beguiling priestess ever since. Overcome by a fit of blind jealousy, Zurga orders Léïla and Nadir put to death.

Alone in his tent at dawn, Zurga struggles with his emotions. Devotion and friendship weigh heavily on his soul. The time approaches when Léïla and Nadir are to be set ablaze on a pyre being prepared on the neighbouring beach. The lovers are led to their place of execution. Suddenly the sky glows red. Zurga has unexpectedly set fire to the fishermen’s huts to distract the villagers from their deadly deed. Léïla and Nadir escape in the confusion, deeply moved by Zurga’s compassion and sacrifice. Nourabad, who has caught sight of the prisoners in flight, shows no such mercy. The enraged high priest stabs Zurga to death. Léïla and Nadir’s voices are heard echoing in the distance.

Shortly after The Pearl Fishers was first revived in 1886 at La Scala, co-librettists Michel Carré and Eugène Corman remarked that, had they known Bizet was to have been the composer destined to write the score, they would have put more effort into their contribution. For all its atmosphere and tragic intention, The Pearl Fishers’ operatic through-story requires a good deal of heavy duty exposition to trigger dramatic events. Calculated discourse and meandering recitatives sprout from every crack. Bizet’s brilliance lies in his masterful ability to subvert the mundane. In the face of his lush, sensual melodies, the obvious shortcomings in this, his “other” opera fail to much matter by the time final curtain falls.

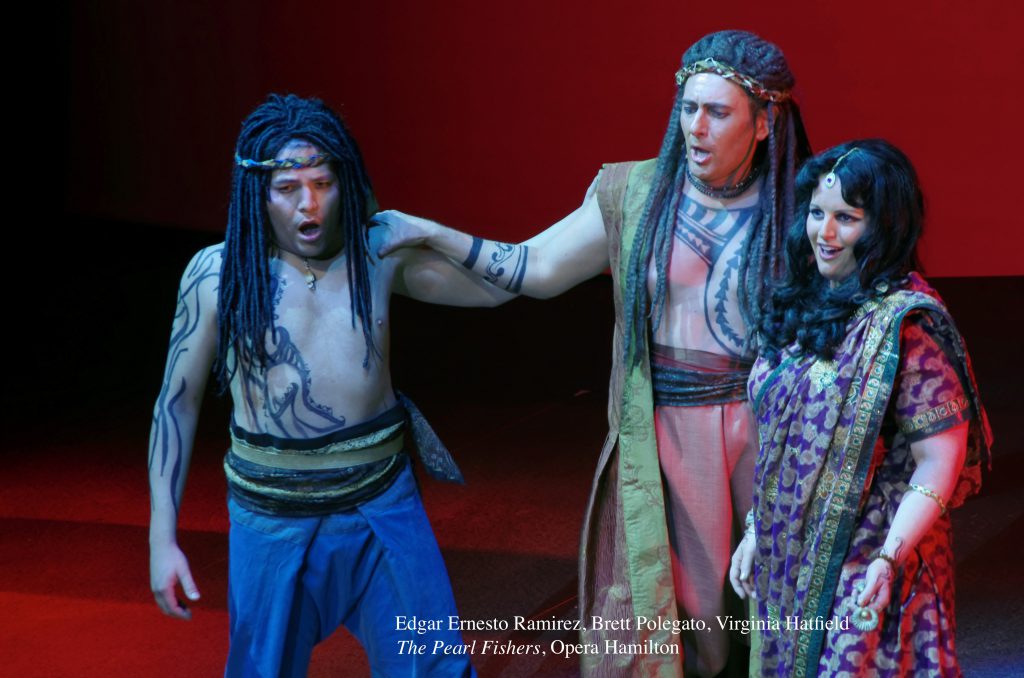

As Opera Hamilton’s Zurga, popular Canadian baritone Brett Polegato gives an astonishing performance, an unforgettable co-mingling of authority and vulnerability, grit and tenderness. His voice is quite simply extraordinary with its towering top and resonant depth, his middle range smooth and lustrous. Like a pearl.

Tenor Edgar Ernesto Ramirez sings the role of Nadir with a gorgeous warmth of tone and exquisite phrasing. This is an artist clearly comfortable working within the classic vocal tradition of French grand opera where lyricism generally trumps show-off virtuosity. This fine young talent can, of course, thrill and does so in virtually each and every one of his many genuinely affecting appearances spotted throughout the Hamilton-originated production. The great landmark tenor-baritone duet Au fond du temple saint (“In the depths of the holy temple”) is performed with an engaging bittersweetness by Ramirez and Polegato, a potent quality that gives the justifiably cherished piece its compelling emotional reverberation.

The Pearl Fishers’ priestess, Léïla, as depicted by soprano Virginia Hatfield is a woman of formidable strength and dignity. Miss Hatfield is a singer actor of great versatility, equally at home in early opera as well as more verismo-inclined nineteenth century repertoire. In Bizet’s plugged-in, highly charged work, the goal is to sing with an absolutely clear sense of emotional purpose, honestly, directly, with great engagement. Hatfield hits the mark with seeming effortlessness. Léïla’s enchanting cavatina in which her love for Nadir overflows in a wave of heartfelt expression, Comme autrefois dans la nuit sombre (“As he used to in the dark night”) becomes a moment of intense beauty in Hatfield’s meticulously focused rendition.

Bass baritone Stephen Hegedus portrays his Nourabad, the opera’s quick-to-condemn high priest, as the dangerous fanatic he is. Mr Hegedus voices his performance in dark sonorous shades. Chilling.

The outstanding ability of its principal cast is clearly this Pearl Fishers strong suit. But the production is not without musical issues. The men’s chorus sings with a profound lack of tunefulness. Conductor Peter Oleskevich could lead with more vitality and dynamism on occasion. Orchestral playing — the rare times it can be clearly heard — could benefit from a bolder depiction of Bizet’s brightly coloured harmonies. But perhaps this is splitting hairs. If a production is ultimately to be judged by the sheer volume of tears glistening in opera goers’ eyes, then Opera Hamilton’s sincere, eager to please Pearl Fishers has to be declared a resounding, standing ovation-worthy success.