Béla Bartók, staunch Magyar nationalist, avid collector of folk tunes, lived in Budapest. Arnold Schoenberg, blunt-spoken intellectual, frustrated portrait painter, lived in Vienna. Each launched near simultaneous opera experiments during the dying days of Romanticism. Both were determined to forge their own unique musical vocabulary, one that reflected the explosive pace of change at the birth of the twentieth century.

With its final presentation of its 2014/15 season, the Canadian Opera Company reunites the two restless Austro-Hungarian modernists in a revival of director Robert Lepage’s classic signature piece, Bluebeard’s Castle/Erwartung. Originated in 1993, showcased again in 1995, resurrected in 2001, the celebrated decades-old production has lost a good deal of the cutting edge zeitgeist that garnered it wide-ranging critical acclaim. Stagecraft and lighting effects are primitive by contemporary high tech standards. Yet, against all odds, the current iteration of this Bartók/Schoenberg double bill by and large impresses.

Bluebeard’s Castle opens the evening with a shadowy rendition of Bartók’s elusive work. Composed in 1911 with a libretto by poet, later pioneering film theorist, Béla Balázs, the enigmatic fantasy creeps out of the cracks of human imagination. The story, loosely based on an old Central European folk tale, is one of good and evil streaked with depravity.

Duke Bluebeard ushers his beautiful new bride, Judith, into his eerie castle. Darkness engulfs them. Spying seven locked doors, Judith demands that they be opened to admit the light of day. Warning her of great danger, Bluebeard reluctantly hands her the first of seven keys. Matching it to its latch, Judith reveals Bluebeard’s bloody torture chamber. Shocked but transfixed, she unlocks the second door. A vast armoury laden with vicious weapons of war is revealed. The next three keys open doors to Bluebeard’s treasury filled with bloodied jewels, his blighted flower garden, a boundless view of his vast domain. Bluebeard attempts to embrace her, promising all that Judith has seen shall now be hers. Blood red clouds begin to gather. Judith struggles free. The sixth key unlocks a door to a lake of tears. Judith wonders what other women Bluebeard has loved before her. Could the rumours that he murdered his former wives be true? When Bluebeard provides no answer, Judith snatches the seventh key. The last door is opened. Three ghostly women emerge, Bluebeard’s wives arisen from the dead, brides of morning, noon and evening. Wrapped in an inky cloak, adorned with a starry crown, Judith, bride of the night, follows those who have gone before her, mystically drawn into oblivion. Darkness descends. Bluebeard vanishes.

The quest to decipher Bluebeard’s Castle has preoccupied commentators since Bartók first publicly unveiled his fevered piece at the end of World War I. Attempts to extract meaning have led to volumes of highly creative interpretation all rooted in dense symbolism and allegory. The work has been seen as a chronicle of love and devotion won and lost radically foreshortened in time. As a window into the depths of the human psyche, the castle’s secret chambers a metaphor for the mind. As a mythical expression of loneliness and alienation. All assessments are valid but none feel completely satisfying. This is theatre noir at its deepest, darkest, most irrational rendered paradoxically dispassionate by Lepage’s stiff, mechanical blocking. Where action is unleashed, the results are decidedly inelegant, the director rolling his Judith bodily down the steeply raked set. Designer Michael Levine’s castle, with its flat expanse of faux stone wall and giant Secessionist-style picture frame further adds to the sense of two-dimensional caricature.

Musically, Bluebeard’s Castle stands on firmer ground. In 1907, Bartók met the rising star of French sound painting, Claude Debussy, who had arrived in Budapest for a series of piano recitals. Bartók was entranced by the young Parisian’s sketchy compositions. Combining the freedom and naturalness of Debussy’s Impressionism with the flexible speech-inflected rhythms and scales he had discovered in local folk music, Bartók set Budapest spinning. Bluebeard’s Castle rings with orchestral inventiveness, frequently expressed more loudly than necessary by the COC Orchestra led by conductor Johannes Debus. Singers are often submerged under a tide of dark-hued harmonies and crescendi played with distinct over enthusiasm, a forgivable fault given Bartók’s compelling dynamism.

Appearing in the opera’s title role, bass John Relyea crafts a powerful Bluebeard, brooding and sullen, his voice a universe of smouldering colours. Bluebeard’s passage from passion to estrangement and ultimate isolation demands a subtle, sure touch from a singer actor. Relyea maintains absolute control, a master of the sinister Duke’s tricky parlando.

Mezzo-soprano Ekaterina Gubanova is Judith, singing a largely reactive role with a pronounced sense of dramatic engagement, arguably verging on overwrought. Gubanova’s instrument, while not exceptionally expansive, is distinguished by a hearty richness of tone and unflagging vibrancy particularly well-suited to Bartók’s urgent, exclamatory style.

If Bluebeard’s Castle is mystery meets melodrama, Erwartung (Expectation) raises the post intermission curtain on a raw, expressionist note. Composed in 1909, Schoenberg’s searing psychodrama would wait almost two decades before it was premiered. Based on an actual case study co-authored by Viennese analysts Josef Breuer and Sigmund Freud, the clipped, 30-minute narrative reimagines the psychotic ramblings of a particularly troubled patient.

Night. A woman arrives at a gloomy forest in search of her lover. Fearful of the darkness, she begins to sing, hoping the sound of her voice will both calm her nerves and alert her missing partner to her approach. Fighting back her anxiety, she advances along a narrow path overhung with menacing branches. Startled by a night bird’s call, she begins to run. Suddenly she trips and falls. A half-hidden form lies sprawled beside her. A body! Calm replaces her panic when she realizes she has stumbled over a tree trunk. Groping her way forward, she comes to a moonlit clearing. The sight of her own shadow frightens her. Something rustles in the grass. The woman flees bursting out of the evil woodland. A house looms in the distance, inexplicably forbidding and ominous. Suddenly, there at her feet, lies her lover, limp and lifeless. She screams for help. No one answers. She cannot revive him. The woman pauses. Her mind flashes back to recent events. For three days she had waited for him to come to her bed but he had abandoned her for another woman, the one with white arms that lives in the nearby house. Enraged, she kicks and slaps his corpse, her fury dissolving into sorrow as dawn slowly, softly breaks around her.

Schoenberg likened Erwartug to a nightmare, an unbroken 30-minute trance, horrific and fluid, scored for a single character, played out in real time. The Woman, the opera’s pivot point, exhibits all the characteristic symptoms fin de siècle therapists chose to associate with hysteria, a clinical label much in vogue at the time. Schoenberg collaborator, librettist/poet/medical student Marie Pappenheim, was deeply distrustful of the diagnosis. A quintessentially feminine condition in the prevailing Freudian view, the notion of female derangement as a release from social-sexual convention served numerous agendas, predominately male. By embracing the Woman as an archetype while still emphasizing her individualism, Pappenheim creates a profoundly complex, intensely sympathetic character. Beneath the ambiguity and rapid-fire outbursts of emotion lies a tangible, tragic tale. Madness and love in Erwartung, as in life, are never far removed.

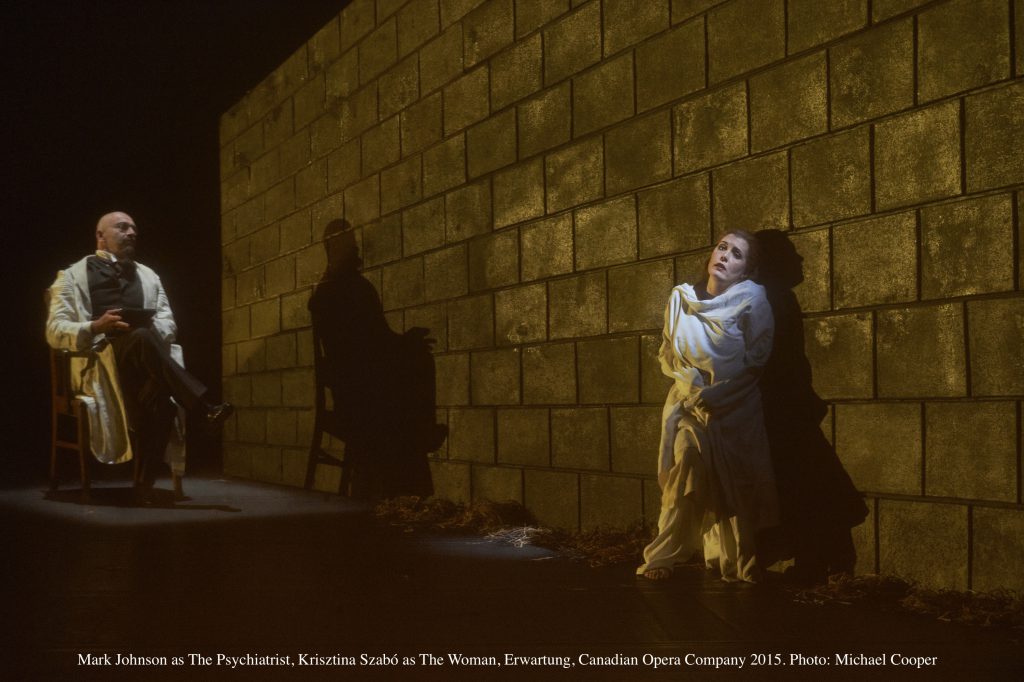

Lepage is at his very best here. Bluebeard’s bland castle wall becomes a vertiginous forest path sprouting a tangle of arms and hands ready to clutch the tortured heroine as she passes. Her lover tumbles out in slow motion. The world is upside down. A blood red moon hangs in the sky. An attending psychiatrist takes notes in the background. Words scroll across a hazy scrim. Kein Tier Lieber Gott, kein Tier (“Not an animal, oh, dear God, not an animal!”) We understand.

A vivid example of early atonality boldly expressed on a grand scale, Schoenberg’s score glows with ever-shifting hues. Allegedly written in only 17 days, the music pulses with diversity, rarely retracing its route. Motifs are fleeting, virtually transparent, rhythmic patterns short-lived. The soundscape is in perpetual motion, the orchestra in constant communication with the central character, supportive at times, challenging at others. Debus and players electrify. But the evening quite properly belongs to Canadian prima donna Krisztina Szabó.

Schoenberg’s writing for The Woman is impossibly taxing, demanding a stratospheric range and superhuman muscle. Szabó more than meets the outrageous requirements, her clear, ringing mezzo forceful, resonant, soaring. This is an astonishing performance overflowing with passion, heartrending in its humanity. Her character spent, released from suffering by a flood of catharsis, Szabó closes Erwartung with Schoenberg’s inexpressibly poignant Liebster, Liebster, der Morgen kommt (“Oh, beloved, beloved, dawn is breaking”). It is a moment, to summon W.B. Yeats, of terrible beauty.

Bartók would begin and end his opera career with Bluebeard’s Castle. Schoenberg would follow Erwartung with a modest two additional theatrical vocal works. Neither composer was particularly at home in the genre. Both are difficult pieces but, as the Canadian Opera Company has demonstrated, not necessarily artistically unapproachable.