Gioachino Rossini suspected his latest opera, The Barber of Seville, was headed for trouble on opening night. His instincts were sound. Years earlier, rival composer, Giovanni Paisiello, had penned his own version of the brilliant 24-year old’s boisterous comedy. The flattering letter Rossini had written to the more senior maestro in an attempt to avert bad feelings had failed to erase his competitor’s resentment. Paisiello packed Rome’s opulent Teatro Argentina with ruffians who whistled and jeered from curtain to curtain throughout Rossini’s premiere. The scene on stage, as bad luck and lack of rehearsal would have it, was almost as uproarious. A stray cat wandered onto the set, darting under the heroine’s gown before being shooed into the wings. A singer tripped over a loose board and had to perform with a bloody nose. The principal tenor decided to ignore the score, making a bravura entrance with a flashy, extemporized serenade. Rossini soldiered on, leading from the pianoforte, fleeing back to his rooms at the end of the performance. Several days later, after a flawless second night, a cheering crowd coaxed him out of hiding. The Barber of Seville would captivate and enchant for the next 200 years.

Showcasing a globe-trotting co-production via Houston Grand Opera, Opéra National de Bordeaux and Opera Australia, the Canadian Opera Company brings a lively, impudent Barber of Seville to Toronto, musically spectacular, theatrically brash. Powered by an extraordinary collection of singers and musicians, Catalán producer Els Comediants’ glossy staging, for the most part, dramatically highlights the wit and charm of Rossini’s playful work.

Based on the first instalment of a three-part Baroque sitcom by playwright Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais, Le Barbier de Séville, reset by Rossini in 1816, followed in the wake of Mozart’s sensationally popular sequel, The Marriage of Figaro, adapted a full three decades earlier. Incredibly, part three in the Figaro saga, La Mère coupable (The Guilty Mother), would not be transferred to the opera stage until recast by Darius Milhaud in 1966. With its wicked mix of slapstick and satire, Le Barbier sets the tone for the entire trilogy.

A wealthy young nobleman, Count Almaviva, has lost his heart to the beautiful Rosina, ward of Seville’s irascible Doctor Bartolo who plans to marry her himself and claim her ample dowry. Enlisting the aid of Figaro, Bartolo’s barber and all-round problem-solver, Almaviva sets his sights on winning Rosina’s affections. After persistent serenading, Rosina emerges on her balcony. Wishing to be loved for himself and not his fortune, Almaviva introduces himself simply as “Lindoro”. The sharp-eyed Bartolo puts an abrupt end to their encounter. Lindoro and Figaro plot how best to gain access to the Doctor’s villa.

While Rosina dreams of rescue and romance, her music teacher, the opportunistic Don Basilio, sparks Bartolo’s decision to marry Rosina at once with rumours that Almaviva is courting her. Figaro overhears and races off to deliver a message Rosina has written to Lindoro. Bartolo accuses Rosina of encouraging the Count’s advances, vowing to keep her under lock and key as punishment. A knock at the door. Lindoro bursts in, impersonating a drunken army officer. Challenges are hurled. The Civil Guard is summoned. Pandemonium rules.

Bartolo grows increasingly edgy. Enter Don Alonso, music student, dispatched by an ailing Don Basilio to conduct Rosina’s daily singing lesson. Bartolo is suspicious. “Alonso”, in reality Almaviva in yet another disguise, promptly produces Rosina’s note, suggesting she be told it found its way into his possession via the lascivious Almaviva’s mistress. The stratagem works. The Doctor is confident he has found a new ally. Rosina is summoned. Figaro arrives, insisting Bartolo be shaved. In the midst of much fetching of towels and throwing open of curtains, the wily Barber manages to steal the key to Rosina’s balcony. Smothering Bartolo with lather, Figaro sets to work while Alonso whispers word to Rosina of the escape plan he and Figaro have hatched for later that night.

Encountering a perfectly hail and hearty Don Basilio, Bartolo realizes the depth of his adversaries’ cunning. Rosina’s ever changeable suitor is likely none other than Almaviva. Rosina must be wed that very night. Basilio is dispatched to fetch a notary. Revealing the ubiquitous love letter, Bartolo convinces Rosina that the Count is trifling with her affections. Disillusioned and hurt, Rosina agrees to marry Bartolo. Outfitted with a ladder, veiled by a furious thunderstorm, Figaro and Lindoro scale Rosina’s balcony. Rosina turns on them both. Lindoro reveals his true identity. Rosina is overjoyed. The Count’s devotion is beyond reproach. The notary is tricked into marrying them. Bartolo barges in with the Guard but it is too late. True romance has triumphed.

Love letters and moonlight, disguises and a knock on the door — Rossini and librettist Cesare Sterbini spin rowdy melodrama from the stuff of timeless farce. Irreverence and anarchy fill the air. A mad carnival atmosphere prevails.

Rossini, master of opera buffa, is at the top of his game here, mocking convention, poking holes in bourgeois morality. Money makes 17th century Seville go round and Almaviva is the ringmaster, scattering fistfuls of cash, turning a none too simple courtship into a dizzy masquerade. Behaviour, good and bad, is generously rewarded. Everyone has their price. Ethics and altruism are pure fiction with, of course, one notable exception. Figaro’s eagerness to assist the Count in his pursuit of fair Rosina is prompted by more than the mere glint of Almaviva’s gold. Bartolo is a contemptible old bully. Time he received his come-uppance. Proud, affectionate Rosina deserves better. A story that might very well have lapsed into bitter cynicism in lesser hands, thanks to Rossini/Sterbini’s indomitable optimism, becomes a riotous quest for happiness and fulfillment.

The Barber of Seville, currently on view at the COC’s Four Seasons Centre, firmly embraces the core values of Rossini’s rollicking text. Bartolo is the clown prince of greed defeated by a noble cause. A flawless theatrical model, however, this production is not. Designer Joan Guillén’s all-purpose set, with its giant pink piano and flashes of commedia dell’arte technicolor, has a distinct circus feel. Spectacle is a given, but scenes all too frequently freeze, becoming little more than rigid tableaux. The effect can be unsettling as director Joan Font accelerates the action, suddenly braking to allow for the inevitable procession of show stopping bel canto solos downstage. The Act I curtain closer is particularly jarring. For all its plumed ranks of military policemen, precarious chandelier swinging and blundering about of servants, the marshalling of events on stage is curiously lack lustre. The mad carnival spirit that generates bursts of forward thrust elsewhere in the production abruptly sputters and loses momentum at the precise moment when Rossini calls for full power. An outburst of questionable robotic break-dancing further deflates what should be the opera’s bubbliest scene.

Uneven as this Barber of Seville’s production values tend to be, ungainly set, 2-dimensional lighting, eerie clownish make-up and hair in particular, the flow of music from stage and pit is superbly consistent.

Rossini’s orchestral writing is bright, nimble and strewn with cheerful invention. The Barber of Seville’s vivid, tonal colours are polished to a gleaming sheen. Winds, often emerging in solo roles, echo and punctuate the story. Violins weave brisk, energetic motifs. The composer’s frisky sense of humour is irresistible. The work is packed with familiar operatic standards, each custom tailored to character — quick-witted Figaro, dashing Almaviva, brave Rosina. Arias, free-spirited and expressive, are rendered with infinitely less formality than were customary for the period.

A vibrant Canadian Opera Company Orchestra under the guidance of visiting conductor Rory Macdonald sets the Barber’s world in motion with an animated rendition of Rossini’s famous overture. The energy and exuberance of players continues to grow as wave after wave of sparkling themes and effervescent harmonies sweep through the auditorium during the course of the evening.

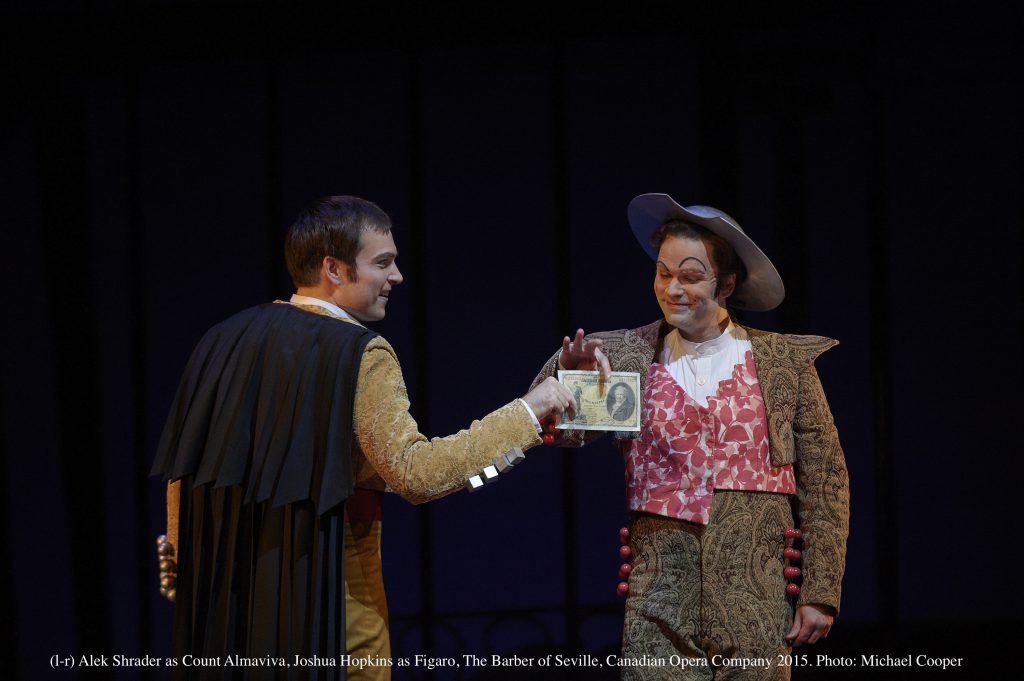

Appearing as The Barber of Seville’s title character, baritone Joshua Hopkins sings a delightfully charismatic Figaro, his appealing, high note-friendly instrument handsomely attuned to Seville’s favourite enabler. Rossini does not insist on an exceedingly big voice for the role but he does demand robustness and great agility underlaid with a warm, rounded tone. Hopkins has all four essentials in abundance. Figaro’s theme song, the legendary Largo al factotum (“Make way for the factotum”), is given thrilling allegro expression delivered at breakneck pace, every “-issimo” tongue-twister accounted for.

Tenor Alex Shrader is Count Almaviva. Shrader is a stylish singer with a lovely translucent top and lavish mid range, giving his voice an engaging ping. Arguably a touch hearty for a Rossinian lead, this fine, accomplished performer cleverly capitalizes on his luxuriant timbre, producing a sound that positively radiates seduction. Almaviva’s celebrated Act I serenade, Ecco ridente in cielo (“Lo, in the smiling sky”), is delivered with skilful ornamentation and great fun. Brave is the tenor who parodies tenors.

Mezzo Serena Malfi sings Rosina, investing the part with a beguiling assertiveness and unmistakeable aura of independence. This Rosina is no passive victim. The rebellious young woman’s measured passage from oppression to freedom calls for a deft touch from a singer actor. Malfi’s sensitive, nuanced performance brings Rosina’s roller coaster emotions sharply into focus. The demanding part, occassionally cast as a soprano, was originally written for a classic 19th century contralto. Malfi’s strong, multi-hued colours and astonishing lower reach bring Rossini’s bold setting to life. Her rendition of the composer’s showpiece cavatina, Una voce poco fa (“The voice I heard just now”) is quite simply glorious.

Baritone Renato Girolami is a burly, blustering Doctor Bartolo, voicing the character with all the gusto and enthusiasm of a true buffo specialist. Bass Robert Gleadow is an appropriately shifty Don Basilio. Ensemble Studio member Ian MacNeil is the Count’s bustling servant, Fiorello. Soprano Aviva Fortunata is Rosina’s eternally exasperated governess, Berta. Fortunata’s heartfelt spotlit solo, Il vecchiotto cerca moglie (“The old man seeks a wife”), fleeting as it may be, is unquestionably a highlight of the production.

The men of the Canadian Opera Company Chorus do double tours of duty, rounding out both Acts I and II as members of Seville’s bungling Civil Guard.

Rossini once famously remarked that every opera he wrote was based on three essential ingredients. “Voce. Voce. Voce.” Given the abundance of truly magnificent singing in this musically magical Barber of Seville, the Canadian Opera Company clearly shares the maestro’s priorities.